Join Shane Gibson as he chats with Jason Taylor a former quant researcher who turned towards the light (or dark) side of data, to explore the practicalities and pitfalls of building data services using AI

Listen

Listen on all good podcast hosts or over at:

https://podcast.agiledata.io/e/building-data-services-with-ai-with-jason-taylor-episode-79/

Subscribe: Apple Podcast | Spotify | Google Podcast | Amazon Audible | TuneIn | iHeartRadio | PlayerFM | Listen Notes | Podchaser | Deezer | Podcast Addict |

You can get in touch with Jason via LinkedIn

Tired of vague data requests and endless requirement meetings? The Information Product Canvas helps you get clarity in 30 minutes or less?

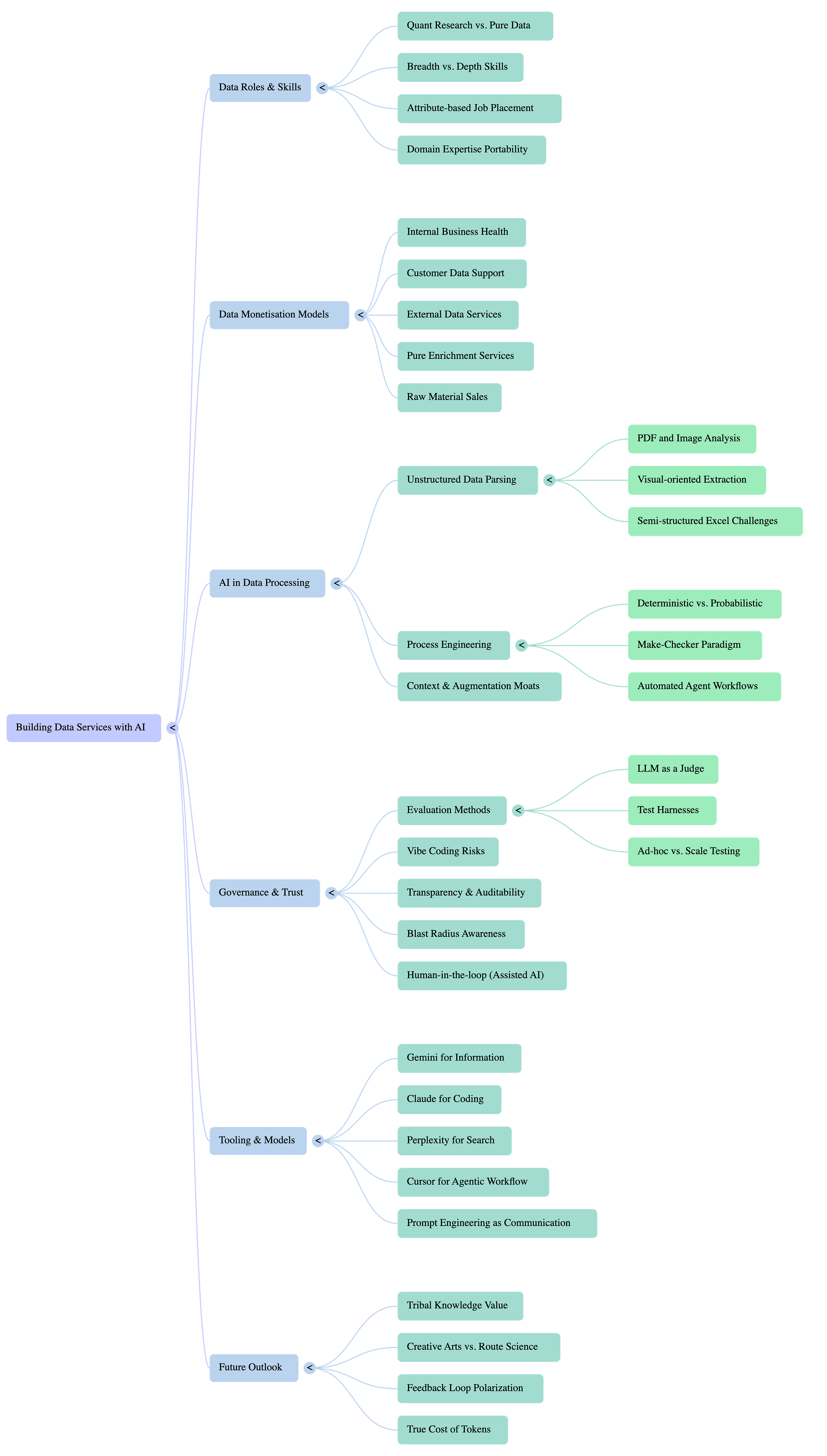

Google NotebookLM Mindmap

Google NoteBookLM Briefing

Executive Summary

This document synthesizes a discussion on the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and data services, drawing from a conversation between Shane Gibson and Jason Taylor (JT). The core thesis is that while AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), has dramatically lowered the barrier to entry for building sophisticated data services—especially in parsing unstructured data—it simultaneously demands a renewed focus on rigorous process engineering, human oversight, and robust evaluation.

Key takeaways include the shift in the data profession from role-based identities to a more fluid, skills-based approach, where transferable skills are paramount. The conversation categorizes data services into three primary use cases: internal business health, customer-facing data access, and external monetization, with AI impacting all three. A central argument is that unstructured data parsing is now a “largely solved problem,” thanks to models like Gemini that can interpret complex documents and even images with remarkable accuracy.

However, this technological advancement introduces significant risks. The concept of “blast radius”—the potential negative impact of an error—is critical in determining the appropriate level of AI automation, from human-in-the-loop “assisted AI” to fully autonomous systems. The speakers warn against “vibe coding” and the tendency to treat AI as infallible magic, citing high-profile failures (e.g., Deloitte, a lawyer using ChatGPT) as cautionary tales. The “maker-checker” paradigm is presented as a crucial process framework for ensuring quality and accountability. The discussion concludes that data professionals must apply their foundational principles of logging, testing, and healthy paranoia to the AI domain, continuously evaluating models and cross-validating outputs to build trust in these non-deterministic systems.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. The Evolving Data Career: From Roles to Skills

The dialogue begins by examining the career trajectory within the data field, highlighting a fundamental shift away from rigid job titles toward a focus on underlying skills and attributes.

1.1. Breadth vs. Depth and The PhD Dilemma

The transition from a specialized quantitative (”quant”) researcher to a broader data professional serves as a key example. This move is framed as a strategic choice between depth (e.g., heavy statistics, requiring a PhD to compete at the highest levels) and breadth (a wider data skillset).

Market Dynamics: The market often favors broader skillsets, enabling professionals to handle more of a project’s lifecycle end-to-end. As Shane notes, “...it’s easier if you’ve got a broad set of skills to be able to pick up a gig or do a role.”

The “PhD Barrier”: In highly specialized fields like quantitative finance, a PhD can be a de facto requirement. JT comments on this pragmatically: “I don’t have a PhD and competing against PhDs sucks.” This has historical roots in the 1980s and 90s when finance began recruiting physics PhDs for their expertise in signal processing, which was analogous to financial market analysis.

Stereotypes vs. Reality: While the market may have stereotypes about needing a PhD for certain roles, the speakers question the universal necessity, pointing out that “not all PhDs are the same.”

1.2. Attribute-Based Career Planning

A core argument is that professionals should focus on their inherent attributes and preferred activities rather than chasing job titles, which can be defined differently across organizations.

Focus on Skills, Not Roles: JT strongly advocates for this approach: “I hate that the role-based mentality... is for somehow perpetuated.” This is reinforced by Shane’s example of survival analysis skills from genetics being applied to supermarket product placement.

Data Persona Templates: Shane is developing a book on “data persona templates,” a skills-based framework. By analyzing job ads with a custom GPT agent, he has found that despite varied job descriptions, the underlying skill requirements often distill down to just three core personas.

Key Quote: “data scientists are just quants, or quants are just data scientists with more subject matter expertise. Like it’s all kind of the same thing.” - Jason Taylor

2. Defining and Monetizing AI-Powered Data Services

The conversation defines a “data service” primarily as a data-centric offering that generates revenue, distinguishing it from internal data teams that support a non-data primary business (e.g., selling ice cream).

2.1. A Taxonomy of Data Use

Shane proposes a three-category framework for the use of data in an organization:

1. Internal Use: Understanding and growing the business.

2. Customer Support: Enabling customers to access their own data (e.g., in a SaaS platform or bank).

3. External Monetization: Exposing data externally to generate revenue, which can include direct data sales or enabling partners.

The focus of “data services with AI” is primarily on the second and third categories, particularly where data is enriched or processed for monetization.

2.2. Models of Data Services

JT outlines several models for companies that sell data:

Pure Enrichment: A customer sends their data, the service does “something fancy” to it, and sends it back. The process is monetized.

Raw Material Sales: Collecting and selling data, often via methods like web scraping.

Integration: Providing specialty knowledge on how to integrate and organize disparate datasets.

Companies like Bloomberg are cited as examples that successfully combine all three models.

2.3. The Impact of Generative AI

Generative AI introduces a new dynamic: non-determinism. Unlike traditional services that sell a predetermined, consistent product, AI-based services sell something that “may be variable at times.” This fundamentally changes the nature of the product and the processes required to ensure its quality.

3. Unstructured Data Processing: A “Solved Problem”

A significant portion of the discussion centers on the claim that AI has made the parsing of unstructured and semi-structured data a “solved problem.”

Key Quote: “the one that’s exploded the most by a massive amount has been unstructured or structured data parsing... I feel like that’s a solved problem. Now do, maybe that’s extreme.” - Jason Taylor

3.1. From Tesseract to Gemini

The progress in this area has been substantial. In the past, extracting text from a PDF with tools like Tesseract was challenging, and even training specialized models like Google’s Doc AI yielded good but not “that good” results.

Now, modern models like Gemini Pro can process complex documents—including financial statements, org charts, and diagrams within PDFs—with “remarkable accuracy.” JT notes his surprise when he drops a document in and says, “give me everything,” and the model understands the content and structure exceptionally well. This has massively lowered the operational barrier to accessing this data.

3.2. The Diminishing Moat of Domain Expertise

Historically, the competitive advantage (or “moat”) for data service companies like Bloomberg or LexisNexis wasn’t just providing the raw data (which is often public), but the “many years of highly skilled and trained... professionals augmenting that raw data... with context.” This organization and curation is what created value.

LLMs are now diminishing this moat. They have “come a long way” and can infer much of the context that previously required thousands of human experts. While there is still value in tribal knowledge—”not everything we know is written down”—the gap has narrowed significantly.

3.3. The Power of Visual Interpretation

A key advancement is the ability of LLMs to interpret documents visually, not just as raw text.

Image-Based RAG: Processing image data (e.g., a screenshot of a report) instead of just the text can be “wildly more beneficial” because the model picks up on subconscious cues like layout, organization, and what else is on the page.

Use Case: Report vs. Dashboard: Shane describes a project where an LLM successfully categorized 8,000 legacy reports by analyzing screenshots. The model learned the human-like heuristic: “If I see a single table of data, it’s a report. If I see multiple Widgety objects, it’s a dashboard.”

4. The Imperative of Human Oversight and Process Engineering

Despite the power of AI, the speakers stress that its non-deterministic and fallible nature makes human oversight and robust processes more critical than ever.

4.1. Blast Radius and Appropriate Automation

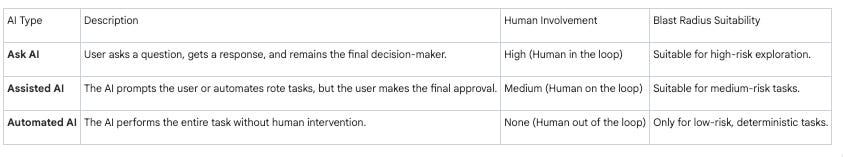

The concept of “blast radius” dictates the level of risk and, therefore, the necessary level of human involvement.

Low Blast Radius: A mistake in a marketing campaign might result in spam.

High Blast Radius: A mistake in pharmaceutical trial data could lead to a death.

This leads to a hierarchy of AI implementation:

4.2. Failures of Blind Trust: “Vibe Coding”

The discussion warns against the dangerous trend of “vibe coding”—uncritically accepting and deploying AI-generated output. High-profile failures serve as cautionary tales:

A lawyer who used ChatGPT for a legal filing, which included fabricated case citations.

Deloitte being forced to repay a government agency half a million dollars after using AI to generate a report that “hallucinated a whole lot of case studies.”

Key Quote: “If you hired a genius level person... Would you read their work after they generated it...? I don’t give a fuck how smart you are. I’m reading what you put together... I’m accountable. So why in any of these circumstances would you not check this stuff?” - Jason Taylor

4.3. The “Maker-Checker” Paradigm

The solution to managing AI’s fallibility lies in process engineering. The “maker-checker” paradigm, a common process in manufacturing and finance, is proposed as an essential model for AI workflows. One agent (human or machine) creates the output (the “maker”), and a separate agent reviews and validates it (the “checker”). This builds in accountability and a review system, much like code reviews (PRs) in software engineering.

5. Evaluation, Testing, and Trust in Non-Deterministic Systems

The conversation highlights a cognitive dissonance where seasoned data professionals often forget their core principles of testing and validation when working with AI.

5.1. The Underinvestment in “Evals”

“Evals” (evaluations) are the AI equivalent of software testing. This is seen as a “massively important” but “under invested area.”

Complexity of Testing AI: Testing an AI system is more complex than traditional code because there are more moving parts that can change: the underlying LLM model (which vendors can update), the prompt, the RAG context documents, and subtle variations in the input data.

Methods for Evaluation:

LLM as a Judge: Using one LLM (e.g., Claude) to evaluate the output of another (e.g., Gemini).

Testing at Scale: Running a large number of tests, including edge cases and “chaos engineering” style random inputs, to understand the model’s boundaries.

Ad Hoc Testing: Even simple measures like asking the same question multiple times to check for consistency in the answers is “better than nothing.”

5.2. Logging and Healthy Paranoia

Data professionals are trained to “log the shit out of everything,” yet often fail to apply this discipline to AI systems. Logging the reasoning path of an LLM is crucial for debugging and understanding its behavior, especially when an unexpected answer is produced.

A “healthy degree of paranoia” is described as a beneficial trait for data professionals. This involves an inherent distrust of outputs and a commitment to cross-validation. JT states, “I still crosscheck things. When I write code with LLMs, I read all of it, like all of it, I see my role as I am the reviewer.”

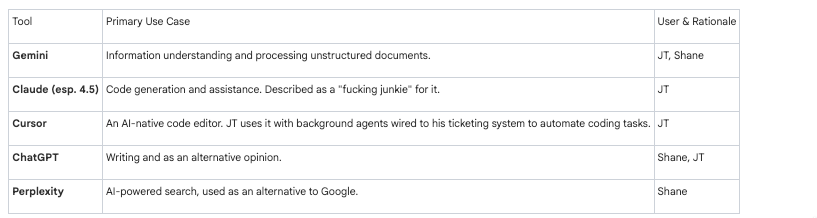

6. The AI Toolkit and Professional Practices

The speakers discuss their personal toolkits and workflows, revealing practical strategies for leveraging AI effectively.

A key professional practice is to always review AI-generated code. A common red flag is when the code references an outdated model version (e.g., Gemini 1.5 when 2.5 Pro is current), which is a “dead giveaway” that the user did not read the code.

7. Future Outlook: Tribal Knowledge and Creativity

The dialogue concludes by speculating on the future of knowledge and human creativity in an AI-dominated landscape.

Gravitation to the Mean: LLMs, by their nature, gravitate toward the mean or average of their training data. This could create a problematic feedback loop where human thought becomes less diverse.

The Pendulum Swing to the Arts: As AI automates more rote, scientific, and predictable tasks (”sciences”), there will be a “pendulum swing” where society places a higher value on uniquely human traits like creativity, randomness, and artistic expression (”the arts”). JT states, “I am very bullish on the arts.”

The Future of Tribal Knowledge: While some may try to hoard their proprietary knowledge behind paywalls, the speakers hope that technology will continue to lower the barrier to recording and sharing information. This could accelerate the advancement of human knowledge, as more ideas are documented and built upon. The belief is that we have not yet reached a point where “all thought has been explored.”

Tired of vague data requests and endless requirement meetings? The Information Product Canvas helps you get clarity in 30 minutes or less?

Transcript

Shane: Welcome to the Agile Data Podcast. I’m Shane Gibson.

JT: I am Jason Taylor, or you can call me jt. Either one’s fine.

Shane: Hey, jt. Thanks for coming on the show. I think today we’re gonna have a bit of a chat around building data services with ai. But before we do that, why don’t you give the audience a bit of background about yourself

JT: Yeah, sure. I guess the simplest way that I usually explain it is beginning of my career was more quant research and data, and then I just gradually went towards the data. I don’t know if that’s towards the light or towards the dark, but um, let’s see. I worked facts at Palantir. Usually everybody wants to talk about buy side, whole bunch of different places.

Now I play in startup land because I have a death wish. I don’t know. Yeah working on a bunch of fun stuff,

Shane: what made you come from Quant To pure data.

JT: That’s a good question. And, and quant is a data gig in a lot of ways, right? And Joe Reese started in this as well, doing more quant research at one point in his career. Like I, I think there are different types of quants but I think a good majority of them, and as people have become more technical over time, they’ve become more data oriented.

Almost like sometimes I joke that data scientists are just quants, or quants are just data scientists with more subject matter expertise. Like it’s all kind of the same thing. But , why I think the very practical answer is I don’t have a PhD and competing against PhDs sucks.

Shane: I think it’s interesting. It’s this idea of breadth versus depth for me. I see people start out with heavy statistics, right? That’s what they love and that’s what they get into, and , that’s a very specific set of skills. And then often they’ll go into breadth. They’ll extend their skillset out and become more data and a little bit less steady.

And , my perception is because that’s where the market is it’s easier if you’ve got a broad set of skills to be able to pick up a gig or do a role and do more of the work end to end yourself than if you are a, a specialist with a really deep set of skills. I hadn’t quite thought about the PhD side, so I suppose, I always talk about, are you gonna be in the top 5% of your skillset? And I suppose and that area, to do that, you have to be a PhD

JT: So first of all, let me start by saying I very much subscribe to the thing you said where I want to capitalize on my strengths and there are certain things I know I’m good at. And actually Google came out with this cool tool where you can actually talk to it about a job and it will tell you it’s all AI oriented, but it will actually tell you attributes and things. I think you like to self describe your attributes and it helps pinpoint potential jobs that it believes in for you. And I, it’s actually really smart and I very much subscribe to this of attribute based or characteristic based job placement, if you will, as opposed to like, you know, there’s a ton of people that are like, oh, I wanna be a data engineer or a data scientist.

JT: And it’s great. Those roles are wildly different at different places. What things do you like to do? What attributes? So long-winded way of saying I very much subscribe to this. I think that there are certain things that I gravitated towards in terms of the attributes I like and the activities I like, like I like being analytical sometimes to a fault, which I think we all do in the data space to some degree. But then I also think the PhD thing maybe a little bit of, terrible history. But yeah, at some point in time, from a finance trading perspective people started leaning into math go figure. And there’s portions of finance that have always been in, in that space.

But at one point, I think it was in like the eighties if, yeah, more the eighties and May, maybe early nineties was when. They started pulling in like physics professors and the like, because people started looking across the aisle effectively and saying, Hey, you’re doing signal processing and studying these things, and hey, that’s the same as finance.

Like it’s the same thing. So people started looking at that type of math and that type of process that they were doing. And that’s, I think people started leaning into that, right? there’s a piece of this which is, I feel and I’m sure this will relate to AI really fast, but it’s just stereotypes, right?

Like people are like, oh, I need a PhD to do this. And I’m like, do you really, do you know what you’re doing? Do you think all PhDs are the same? But ultimately that’s a good chunk of the market. I’m not gonna discredit people having a PhD. I think that’s awesome. I definitely. Feel like I would’ve wanted to do that at some point in my life had I not made certain decisions.

But yeah it’s hard. There, those people are smart and it’s, especially on paper from a recruiting perspective you know how it’s some recruiters are just like, oh, here are the qualifications I was given, yay or nay. And that’s like

Shane: I think I think the recruitment process is broken. I think that whole industry is gonna be disrupted. I think we’re gonna move to more community or closed network based recruitment. Very much

JT: Aren’t we there though? Aren’t we already there?

Shane: yes we are for some, but yeah. If I look at, over here, the way the government over here recruits, my standard joke is somebody in a government agency generates a job request job description with ai, to which then the candidate uses AI to generate the CV to match the job ad to which then the recruitment agent then uses AI to see whether the CV matches the job ad, I was talking to somebody and they were advertising for an administrator. Office kind of administrator’s part of their process. And they were saying they had five perfect cvs, perfect matches all the experience, all the skills. And when they went to interview them, none of them had done anything near what the CV said they had.

So I think this personal recommendation, this personal network is gonna become more and more important. And the idea of skills \ being transportable. I remember many years ago when I was working at SaaS and I was watching one of the projects, one of the consulting teams did for a supermarket.

And they ended up using survival analysis to figure out placement of take away hot meals with something else. And, I didn’t do well at stats at school. I didn’t enjoy it. So it was always funny when I went to work for a company that was pure statistics. And I was like how does this work?

And they said imagine you got, a tall man and a short woman, and they have a child. They, there’s survival statistics on, which genes are gonna survive and will the child be tall or short? That’s what we use to decide whether we should put beer or Coca-Cola next to those meals.

And I’m like, I still don’t understand it, but it makes sense. And so it’s this idea that actually, like you said with the finance stuff, these skills you get in another domain and then they are really useful in an alternate domain. So focus on the skills, not the role.

and that’s where the value is. Yeah,

JT: Yeah, no, a hundred percent. I hate that that’s perpetuated. I hate that the role-based mentality for a lot of people is for somehow perpetuated that’s just how people think about career

Shane: I’m currently perspiring on my second book, which is around data persona templates. And so one of the things I’m doing is I need examples for the book. So what I’ve started doing is downloading job ads for data professionals. And then I’ve created basically a chat GBT agent based on the book for a whole bunch of prompting.

And I’m telling it to take those job ads and create the persona template for me.

And the persona template is skill-based, it’s all about skills. It’s really intriguing to take all these different jobs that look different, and then when you boil them down to what is the persona it typically comes up with only three,

Three core ones, there’s variations of it, but I’m intrigued by that. But this one’s not about data personas. This one’s about building data services with ai. Why don’t you explain what the hell you mean by that? And we’ll go from there.

JT: What do I mean by that? There’s a very easy rabbit hole here, which is like, what is a data product, which I’m going to avoid. We are not going to go down that hole

Shane: Ah, come on. Pedantic semantics says 45 minutes of us arguing a definition of a definition.

JT: Terrible. No, I’m not playing that game. What are definitions, Shane? Can we, yeah. Define definition. . If you ever see Joe Reese, make sure you ask him to define definition. Joe loves debating semantics if you didn’t know that already. So if you see him or hear him please ask him these questions.

He loves them. Anyways no. I’ll start with an interesting divide that I was actually talking to someone earlier about. I always find it interesting because the vast majority of the data space, usually when you talk to other people in data professions, they’re usually in some sort of supporting role, I’m gonna call it. And when I say supporting role, I mean that the data itself is not the revenue generating aspect of the company, Very basic examples. I work at a company that sells ice cream, so I help ‘em figure out how to best sell ice cream. But still the main thing that you’re selling their ice cream, right? There is an entire world of people like us that sell data. And I’ve lived in that world for a very long time. It largely focuses around things like finance, because finance is an industry that has to consume data in order to operate. There are other industries, I think marketing and advertising and things like that are also in, in this scope.

But there’s an entire industry of people that just sell data. So I think that, especially from a data services with ai, I think of a couple different things. There are the people that are pure enrichment based. Send me your data. I will do something fancy and send it back to you. There are the people just selling the raw material. Here’s the data I collected in some capacity. A lot of those people are doing web scraping, not all of them. And then there’s other people that do integration style work, and if you think about a Bloomberg, which is relatively a household name at this point, they do all of them, which is interesting, right?

They’re both consuming from the public domain. They’re also have, specialty knowledge around how to integrate the data, and then also how to enhance it if you give it to them. But now we’re in a new world, not to say generative AI is brand new. I think it’s relatively common knowledge.

Maybe not for everybody that generative AI’s been around for a little while. It’s just now very mainstream, very accessible. There’s 10 cajillion startups around it. But it’s very interesting because , of course the key. Aspect of it, which is it’s non-deterministic. So now I’m not selling a predetermined thing to some degree, I’m selling something that may be variable at times.

I think that, especially, services around AI today, there’s definitely no shortage of web scraping companies. , I think the one that’s exploded the most by a massive amount has been unstructured or structured data parsing, that’s exploded. And I feel and I’m curious of your opinion, and I’ll pause here. I feel like that’s a solved problem. Now do, maybe that’s extreme. Do you agree?

Shane: I think it’s like when people tell me data collections a solved problem. And every time we onboard a new customer, two or three of their source systems ones we know will and then there is always an outlier system where there’s a hundred customers in the world and the APIs are really badly documented.

And the data structures are a nightmare for us to try and understand. And I sit there and go solve problem my ass. I just wanna go back though. There’s there’s an interesting one. One of, one of the things I do when I kind of work with companies and I’m helping teams out we start this idea of this playbook.

And the idea of a playbook is basically a bunch of slides and they have two purposes. The primary purpose is to explain how the data teams work for any new data team member. So when you onboard, you read this and you you get a feeling of how they’re structured, how their workflows, what the culture of the team is.

And the second one is if you’re a stakeholder in the organization, it tells you how the team works so you understand how to engage with them how long you’re gonna pretty much wait, what your role is and that data work. And one of the slides that becomes really common for me now, right at the beginning, is saying that I can categorize use of data in three ways internal use to understand the health of the business and grow the business data to support the customers where the customer’s actually accessing their own data.

So typically as software as a service or a bank or insurance company. And the third one is where data is used externally for monetization. And that might be selling data that might be enabling partners to use whatever you have. If you’re an insurance company and you’ve got insurance agents out there that I treat that as external data, you’re giving them access to that data outside your organization based on your customers to make more money.

So I kind of like that framing, so what we are talking about when you talk about data services with ai, you are talking about that last one, data being exposed externally, securely to make money somehow. And it may not be selling data, but it’s definitely we are exposing that data and sharing it to monetize it.

Is that what you’re talking about?

JT: I think that is definitely correct. I also think it’s the middle one too which is like exposing their own data, if I heard that correctly.

The exposing their own data, I think is another one. Like a very common is just enrichment, it’s already my data. You may be adding or doing something to it, that then I’m monetizing the process as opposed to the data itself.

If.

Shane: Okay. I heard a podcast a while ago that was intrigued me, and it was around a massive US company that had digitized and augmented all the lawyer case study ti case history, thingies can’t remember which one it was. I seem to think LexisNexis, but I’ve probably got that wrong. And what was interesting here, what was interesting was, and it’s coming back to this idea of semi-structured or structured what they were saying is,

JT: too.

Shane: Yeah. You define definition. Actually, I have a definition of a, and then I was doing a group thing with Ramona and Chris Gamble.

And Ramona and I have a disagreement on the definition of structure that unstructuredand And it’s all around csv, right?

Anyway so what’s interesting about this is you think okay, we’ve got all this case history stuff, and it’s in books and there’s probably digital versions of those books. And so it’s a sole problem. Now I could go and grab all that content and digitize it and create a service that competed with them.

And yes, they’ve got market share. The, how do I find the market in that, potentially, but I, I get the impression it’s not cheap, it’s for lawyers. Nothing with lawyers is cheap. So I could probably disrupt them and Uber them, or Netflix them right?

JT: Yeah.

Shane: What the key was the augmentation.

It was the many years of highly skilled and trained legal professionals augmenting that raw data, even though it was unstructured with context and that context is where their moat was. So before we get onto, , that idea of, is the problem solved? Is that what you are seeing though, is that once you get this data and then you add additional context to it, that creates the value, that creates the moat. That’s harder for anybody else to actually go and breach.

JT: Yeah I’m just gonna start outright by saying yes, I agree with that, and I think that’s, again I’ll refer to Bloomberg, FactSet, s and p, et cetera, because that’s the world I know, which is, public company filings are public, right? You can go and you can download Apple or anybody else’s, 10 K or Q or whatever other filing. Cool, neat. There is some value there in being able to access that and make it easy to consume and blah, blah, blah. No discount to that. And there, there’s actually cool open source people doing that Exactly now, which I’ll come back to. But yes, I the work that they do to organize it, right? To your point on semantics and governance and all this stuff, it’s that organization that actually gives value to the data.

it’s not about just serving it up, it’s about making it usable with other stuff, or potentially integrating it, so on and so forth. So and is that all hardcore domain expertise? Some of it, not all of it. I imagine in the legal space it is far more, but the part I would want to come back to is that getting access to the data and the value provided in that just operationally dramatically lower, massively lower.

I don’t think anybody disagrees with that. I think that that integration, that domain expertise has also become more accessible. I think that even though, in that particular case, and maybe it was Lexi Nexus or something, has all these domain experts there I, I do also think that, lMS have come a long way. They can infer a lot of these things. It doesn’t mean they’re perfect, but it does mean that we’ve accelerated what usually took hundreds or thousands of individual people to fill those gaps. So the moat has diminished significantly.

Do I think that there’s still differentiation or IP and domain expertise? I absolutely do. things I’ve been talking to people about, like I I’m very comfortable with that idea. There’s a very basic idea, right? Not everything we know is written down, period. it’s just not written down, or it’s a little bit more out there. And at the end of the day, large language models, for the most part, gravitate towards a mean, that’s by definition what they do. Do I think that means they can’t learn these things? Not really. And I’m using learn very loosely in that context. Do I think it means they can’t learn these things?

Not necessarily, but I do think the tribal knowledge, et cetera. This is what people are trying to do with rag everything else, right? It’s just how do I shove my tribal knowledge into the thing so that it has the things it needs to do this. But yeah I, that is definitely what we’re talking about.

I think that the expectations and obviously what you can accomplish today is wildly different. And I think that especially from what you can do, the bar is tremendously lower. But I think the expectations are wildly off the chart. I think to the earlier point, unstructured versus structured There was a period of time when shoving a PDF into pick your favorite model, whatever that was sucked a lot. Even if the PDF was pretty modern, you could extract the text off great, cool, still not great. And we’ve come a substantial distance from that where, I, on a regular basis am processing PDFs just as things I’m doing as part of my day to day. And I really like Gemini. I’ll plug them. I don’t mind. I really like Gemini’s Pro model for the vast majority of things that I plug in there and bear in mind, these are all kinds of interesting financial statements from a variety of different providers. It could be org charts.

I’ve found org charts in there, which has been cool, diagrams, all kinds of weird shit. And they, with remarkable accuracy, just pull it off. And my favorite part is that, and not that I’m doing this professionally, but I think the first thing I always try and do just for absolute giggles, is I drop the document and I say, give me everything. And then I’m just like, let’s see what happens. Fuck it. Let’s see how good or how well it understands things. And I’m continuously surprised because, it wasn’t that long ago that, again you’d have a tesseract or one of these other platforms that’s very widely used and , widely accepted.

And even if you trained a model like Doc AI or any of these things, they were good, but they weren’t that good. Like I couldn’t just drop random shit in and be like, Hey, gimme, gimme the stuff. And then That’s awesome.

Shane: I remember zero days when, we talked about dropping an invoice or a receipt and having it just turn up in your accounting system with accuracy. And this is 10, 15 years ago from memory. Back then it was a hard complex problem.

Now it’s not. One of the things I think we’ve gotta be really conscious is, is this idea of blast radius.

So what I used to always say in the data space, ghost of data past is, I’ll work on a marketing campaign. Because, the data we’re gonna get is gonna be crap, and therefore the results we’re gonna get are gonna be okay for moving a lever, but they’re not gonna be accurate. But if I was working on pharmaceutical data for a drug trial, then , it has to be different because the blast radius are getting that wrong.

When somebody dies, the blast radius of an incorrect marketing campaign is you spam somebody. And I think this is gonna be the same with using AI against data services. The standard, you’ve heard about, probably heard about the one where a lawyer used AI for the thing to the judge and Yeah.

And and there’s a use case in Australia where Deloitte’s had to pay back half a million dollars to a government agency because they used AI to generate their very expensive review document. And it hallucinated a whole lot of case studies. So I think we’ve gotta be careful about where we use it.

But I can see that the domain knowledge it has now from all the data and tribal knowledge it stole is useful, right? If the blast radius is acceptable, that actually it’s good enough to look at that, apply some context and it’s cheaper and faster than a human doing it, and the impact of it being non-deterministic and getting it wrong.

JT: But on that note, and let’s, we can tie this easily back to governance and among other things and the, I guess the world that I’ve come from is very easy. In a lot of contexts to generate, I’ll use the Deloitte example because it’s fun to pick on them, to generate a report and just shove it out the door. Why do you do that? Fuck if I now, but it’s very easy to do that. And this is my current complaint with vibe coding as well, right? It’s just that people hit the button, they say, ah, it’s fucking magic. And then they shove it out the door and it’s for the love of God, do you read your prs?

Do you edit your own writing? Please go back and read what came out of the random black box. Places I’ve worked, especially, when we were at Palantir’s amazing. At shipping things fast, right? But I was with a bunch of people, I won’t say where, but like I was with a bunch of people.

I’d have to kill you if I had told you where. But and they were phenomenal engineers, very good at understanding the problem write code very fast. And I caught a couple times where I’m like, guys, just read each other’s stuff. Like it’s not, it doesn’t take, I promise it doesn’t take that long. And then, we got there really quickly. It wasn’t a big deal, but and they’re, again, all exceptional. So it was a fairly easy thing to do. But I know tons of people that are engineers that don’t read their prs or don’t have automated checks in place, or not linting, like all this.

Do you use Grammarly? If you write do you spell check shit? Like for the love of God? If you’re writing a paper that has citations, fucking check the citations. This is like basic stuff, and I think that people are getting so jazzed about the fact thinking it’s literal magic and just forgetting everything.

They’re like, what planet am I on? Hit the send button. Go for it. And it’s just yeah, just take. You saved 90% of your time that you would’ve otherwise spent writing it. You can spend another couple minutes just making sure it didn’t spit out garbage. And, I’ll rant on this for two more seconds.

If it was a person, if you hired a genius level person, let’s assume that you hired somebody tomorrow to help you with your job, that is a certified genius. Would you read their work after they generated it or would you just say here, okay, cool, and just submit it to your boss or your customer? I don’t give a fuck how smart you are. I’m reading what you put together, right? I need to know what it says. I need to know what I’m represent I’m accountable. So why in any of these circumstances would you not check this stuff like that? It just, it’s mind blowing to me

Shane: It’s an interesting one because as we know, l LM is non-deterministic. And so people go how do you trust that it’s doing the right analysis? And Juan Cicada had a great comment many years ago where he said how do you trust the human?

And I sat there and I was thinking, yeah, the number of times I’ve seen a data analyst come up with a number and nobody peer reviewed it, and we trust it because a human wrote some code, and I suppose the code’s deterministic, you can go and see the code and run it time and time again and get the same response right or wrong.

That response is, but it, that’s not the point. The point was you trusted that number, made a business decision and nobody peer reviewed the process or the code. And I’ll go back to , one thing you know is definitely with ai vibe coding at the moment, if you wanna see how dangerous it is. We’re a Google platform, so I love Google.

Actually I love their platform. I love their technology. I hate their partnering and I hate their marketing ‘cause it’s the worst in the world. But anyway just go on to Reddit onto the Google Cloud subreddit and watch how many students are going and buy coding with the Gemini API and pushing their code to a public Git repository and then getting whacked with a three to $30,000 bill within two days because their API key is publicly available and people are just scanning, get repos and grabbing those keys and slamming them.

Somebody should run their eye over the, and it’s like you just watch the unintended consequences of this democratization. But let’s go back to that image one. ‘Cause it, it’s interesting for me. So one of the things we did with one of our customers a while ago, they were moving from a legacy platform to a new data platform.

And they had, oh, I can’t remember what it was, but something like 8,000 Cognos dashboard reports. So they’re built over 20 years and

JT: People watch every single one though too.

Shane: They’re all active. When they asked which ones could we get rid of, the answer was none. And they’d spend a couple of months with a small team of really good data analyst bas trying to document them.

So all they really wanted to understand was how big’s the data estate, right? H how many of these do we have? What do they look like? Which ones do we migrate, rebuild, or migrate first? Which ones don’t? And what we ended up doing is we ended up building a tool called disco. Effectively they exported out all the Cogness reports as X ml.

Yep. That was definitely a disco

JT: I’m dancing for anybody

Shane: Uh, that’s right. Yeah. I have a habit of making t-shirts. So we have a T-shirt for 80 80. The disco people can buy it online if they really can. And so what we did was they basically pushed the XML files to us and then disco when and scanned it.

And we did a whole bunch of prompt engineering based on some patents to say, what’s the data model underneath them? What’s the information product canvas? What action and outcome do we think’s been taken, right? So we generated all this context and then pushed that back into a database so they could query it.

And that worked, right? There was some engineering we had to do because doing it for one XML file manually works, do it for a thousand repeatedly. You have to loop through. But the blast radius was small, right? Because really what they wanted is insight. And then what happened was they came back and they said, we documented the reports that were copied,

so this report looked like that report, but it had a new filter. And this report looked like that report, and it had one more column. So where people had just cloned the report and that helped them deju. But they came back with an interesting question and they said can you tell us which are reports and which are dashboards?

JT: Oh,

Shane: So, Hmm. Okay. And there was some business reasons why they wanted to do that. So what we tested was them uploading screenshots of the reports, dashboards. And what’s interesting is, yeah, Gemini and I think this, were back then, we, this is pre-pro 2.5, but even then it was good. It basically.

Did what a human did and said, if I see a single table of data, it’s a report. If I see multiple Widgety objects, it’s a dashboard. And it went through and categorized them and I was like, holy shit, that just makes sense. And the other thing I’ve been doing is uploading the information product Canvas as a screenshot.

So building a canvas with a stakeholder, taking a screenshot of it and putting it into the lms and then saying, give me the metrics, give me the business model give me a physical model. A whole lot of questions around it. Whereas in the past, what I’d do is scrape out the text for that and put the text objects in, whereas now I can just put an image in there and I get almost as good a response.

Now the key is the blast radius for what I want to do is understanding, , I want to understand quickly versus I’m not gonna go tell it to build an information product and deploy it. But yeah, I cut out a whole lot of effort and it feels magical.

JT: So I’m gonna, I’m gonna do two things. One yeah. Image based LLM use is awesome. I saw someone recently note how we’ve been talking about rag, but doing it purely on I image data as opposed to on the text itself has been wildly more beneficial. And that’s because, there’s subconscious cues there, there’s things that we pick up on when you look at the layout of the text, what else is on the page, how the text is organized.

And it’s not just about looking at the text itself. And that’s been hugely beneficial. So that’s, whenever I do data file processing today, extraction, structured, unstructured, that kind of stuff, it’s all visual oriented. I try to avoid scraping entirely. Now, I’ll give you a kicker, which I don’t think this is IP at all, but like a kicker is a Excel.

I can’t pdf an Excel document that’s just extra stupid, right? You can’t do images of Excel. But Excel is a wildly interesting thing. This is where we can get into structured unstructured, right? Excel under the hood’s, really what XML or that weird format that it uses, right? In all I would define that as semi-structured.

Other people may fight me on this, that’s fine. But I would define that as semi-structured. Because it has structure inherently, but it’s also variable in nature. So I consider that semi. But those documents are hard to understand because, hell, I’ve seen too many really shitty financial models that are just like 20 tables in one tab and I’m like, oh, for the love of God, why did you do this? Who are you and what kind of chaotic person? Organize your shit, like gimme a break. This is insane. No. Scrolling around thousands of rows left or right. This is wild. And you’ve seen these, like people build financial models, just the most ass backwards ways on the planet. But visually interpreting them, assuming that you can get away without the pagination or anything like that is, very good. It’s way better from a visual standpoint. But I think that the big thing, and I’ll circle it back to the main topic here, If you think about, now there are companies out there that sell data where, that have a data oriented process, right? And that is their main revenue driver. And then you think about shoving a large language model into that process in some capacity, mostly probably because it’s unlocking some new features for you, or you’re moving faster, you don’t need humans, blah, blah, blah. In some ways It’s not really different than it was before. And I know that sounds really weird to say, but the reason I’m saying that is because if this is your product you always had, whether you acknowledged it or not, you always had a need to set up proper process to ensure you have a quality product. So for me, when I think about large language models and their use in any of these processes, it’s all process engineering. Yes, context engineering, blah, blah, blah, blah. But like it’s process engineering really that we’re talking about. And especially. Once you start talking about multiple agents, I’m air quoting agents because that’s a different bag of tricks. But once you get, multiple autonomous processes interacting, like it’s all process architecture, right? You’re, I think the most common one that a lot of people talk about is a whole maker checker paradigm of you make it, I check it. That’s how it works forever and always.

We don’t cross lines that works reasonably well. There’s some sort of, accountability structure and review system and so on and so forth. Prs have the same thing and people still put in shitloads of additional automation, but it’s process structure, right? So even if my entire data product just for hypothetical sake is me just. Shoving a prompt and hitting play repeatedly and then sending it to somebody , you should still have some sort of review system. You should still have some sort of checks to make sure it’s not garbage, every major manufacturing, et cetera. Everybody has this and that’s why like, I still think the lawyer and the Deloitte example, I’m sure the PowerPoint Deloitte put out was huge and it had a billion references and it was blessed by the Pope and shit.

Like I, I’m sure it, it had all this stuff so it probably make it really hard. But we’re data people, right? Rip all the fucking things off, go cross validate them with a deterministic process flag. The ones that don’t like you, you can bootstrap your probabilistic process with deterministic shit.

It doesn’t have to just be like, everything’s tossed to the wind where you’re using a new tool just hail Mary and pray. It makes money and VCs will pay you I don’t understand that mentality, we’ve been doing this for a long time.

I am definitely the first one out the door to use AI and LLMs for things, but it doesn’t mean I’m gonna let it, drive my car care for my kid. Like I, I want

some structure and controls around no different than a human right? And I think it’s a lot of people poo poo the idea of treating LMS as human , making them human-like. But I think that it’s a very good analogy, it corroborates my feeling towards vibe coding, which is , why in the fuck would you approach an engineer and just say, build me a website, and walk away and think it’s just gonna work.

Like they’re gonna build something.

Shane: it’s even, worse now though, because you read people saying, my boss vibe coded over the weekend and gave me the code and told me to push it to production. Like there, there’s a problem.

JT: I have a feeling that’s clickbait though.

Shane: Yeah, probably. Although, I’ve met some managers. One of, one of the questions I’ve got around that Deloitte thing though was the first prompt in their agent always you telling it what the latest shape to use in the document, I like where pyramids this week or where circles or where matrixes, because you gotta change the shape of every document that, that was dark as.

And by the way,

JT: That’s where all the money comes

Shane: the interesting thing is this idea of make a checker. Is that what it make

JT: Make? checker. Yeah. It’s a process paradigm.

Shane: yeah. Is around factorization. It’s about repeatability. It’s around deterministic.

And then we have artists, we have craftspeople that make things that are just one and done. they make it once and it is not deterministic.

It is probabilistic. It is a piece of furniture

JT: I’m gonna fight you on this. I’m gonna fight you on this. I agree with you that if I am painting a painting, that it is easy to think about. I’m painting the painting and it just, I paint it and it’s over. But I don’t know, I don’t know if you do any art Shane, but I cook I’ll relate this to cooking. Do you cook?

Shane: Yes.

JT: Do you taste your food while you’re cooking?

Shane: Yes.

JT: Good. That is a good thing you should do. It’s not exactly make checker, but if you have a partner or someone you’re cooking for, sometimes you have them taste it, It doesn’t mean you have to have them check it just at the end and you get to redo the whole fucking thing. But at least having some process that ensures you are not going off the rails entirely. I make a lot of random stuff. A lot of the stuff I make I’ve never made before just because it’s fun and I always taste it midway through because you never know what might go wrong or you might, there’s little tweaks, more salty, more spicy, too spicy, that kind of stuff. But the make checker paradigm, I. that is a very particular paradigm . There are probably some ways that that Pattern is implemented where it’s you finish your thing, give it to me, I review, say whether you suck or not, hand it back to you. Might also be versions of that where it’s mid points,right? Like

Shane: Okay so let’s take that, make a checker idea and say that the process, that even an artist, a craft person checks it themselves, right? They may have another person that’s as experienced as them, or, but they are checking, right? They always checking their work.

JT: Hopefully to some degree.

Shane: And within, gen ai, I have three types.

I have what I call ask ai, which is where you ask it a question, you get back a response, you ask a question and you’re chatting with it. And then you go off and make the decision as a human, right? And ideally get another human to, to check your work. Assisted AI is where it’s watching what you are doing and it’s going based on what I know, you might wanna think about this,

so it’s prompting you. You can listen to it, you can ignore it, but you carry on, you finish that task. And automated AI is where the machine does it and no human’s ever involved. Yeah. It just happens. And so if we take that idea of PDFs And if we think about code being deterministic And LMS being probabilistic, and we think about if I wanted to just upload a PDF and get some tribal knowledge back about it. That is a probabilistic problem

I can put it up there. I’ll give you some stuff. I’m in the loop. I’m gonna make some decisions. So therefore it’s an ask kind of feature and the blast radius of me getting it wrong lives with me,

and am I make checker paradigm. If I was automating that PDF to go into my finance system and put in the number, then maybe I move to an assisted model, I upload it. The machines identifies all the fields for me. It comes back and goes, this is invoice number, this is the tax amount, this is the total amount, this is the supplier.

You happy, click go. So it’s a system, it’s automating all that Rossi ship, but I’m still making the final call of Yeah, that’s right.

Versus if I take it to fully automated. That’s when I’m dropping in a thousand invoices. They’re going into my finance system and a payment has being made, and I am not in that loop.

At that stage. In my head, I go back to code, I go back to deterministic code that is looking at specific places on the layer of that invoice and saying that is the number, and if there’s no number there, don’t take it from anywhere else. And so I would say at the moment, I would not use an automated gen AI solution in that use case.

That’s only because I haven’t tried it lately. Like you said, when I uploaded images two years ago, it sucked. I upload them a year ago. It’s got amazing. I haven’t, done it this week. It’s probably gonna freak me out. So where would you sit, right? When do you jump from assisted human in the loop?

Make a checker to let the bloody thing take this unstructured or semi-structured data and just human out of the loop.

JT: I’ll say a couple things. One, there’s the very obvious part that I’m gonna state because everybody’s gonna say crap about this, but security, obviously there’s a security element to this. We’re talking about financial statements, blah, blah, blah. Let’s remove that just for argument’s sake. So I’m gonna repeat again, we are removing the security concern here and the data privacy and all that shit, just to have a hypothetical conversation before people are like, eh, privacy, blah, blah, blah.

Shane: But hold on. What’s your definition of security?

JT: ask you, go call, call. I’m gonna give you Joe Reese’s phone number. You can call him. He loves to debate semantics. Anyways this is gonna sound funny. I don’t know where that line is, and I am actively and consistently trying to do it the automated way as much as possible, and I often equate a lot of these things to like meditation, right? This is all about building good practices. You have to set up the conventions in your mind, build the muscle memory to do the thing that you may not have done before. I’m with you it’s very easy for us as engineers to think about Hey, I wanna rip this one cell.

I know it’s in the same place every time off this document. Write the code to do it right? And don’t get me wrong, there’s an over-engineering element to this of throwing an LLM at a problem like that is definitely a bazooka. At an anthill, like a hundred percent. There’s also a time to market, I’ll call it component of this, which is how fast can you write that code compared to how fast I can go to a website and upload a file and ask a question.

I’ll quick draw with you and I’m willing to bet that I’ll win. And I’ll still get the same answer, right? And then there’s a middle ground if you really wanna fuck around, which is have the l lm write the code to do the deterministic thing. That’s a whole nother like I don’t have to have the LLM just do the work. I can have the LLM write the process to do the work. And then you get a little bit of, a little bit of both, Because it’s a deterministic process that was generated very fast. The, this whole name of the game is speed, how fast can I do X activity?

That’s our North Star. If we’re talking about expense parsing I literally just did this the other day, right? I dropped a PDF onto a platform and it read in the expense. Cool. Did I validate it? I didn’t actually, that’s not entirely true. I knew what the number was before I dropped it in and it happened to produce the right number.

And I was like, cool. So that’s my pseudo maker checker. Most of these platforms these days. And you made a comment before about. Trust. And trust and determinism, trust and code, right? Especially when we think about people. A lot of that trust is just based on transparency, Transparency, auditability, the ability to go back, And this is a very common paradigms in data. Like, how do I roll something back? How do I undo something? We were talking about this yesterday or the other day, right? Especially, from a version control has given us this wonderful sense of security. I can go back, I know what happened, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, I can yell at Shane ‘cause Shane fucked it up. So we have blames. I think that, in this world where an LLM can do the work for you, again, from a cutting down time perspective, it does cut down the time. Maybe I put the document side by side with it, which is very common, of the old platforms and the new ones, Great. Look at the document. Here’s the value, here’s where the value came from now. Looking at a form, let’s just make this more complicated. ‘cause it’s fun, If it’s a financial statement, And there are a bunch of companies out there that just straight do this.

This is their business, right? Talking about AI data services. Their whole job is to take documents and PowerPoints, I won’t name names, but documents from investment funds as an example and pull off the values. Now there’s definitely an intelligent person out there saying, why the fuck don’t they just put the values out on an API?

And that’s a great question, but that would be logical and God knows none of this shit makes any sense. I know a lot of them put out these documents and they probably got fucking pictures on it and all kinds of stuff, and they’re, and hell, if they’re all the same, they’re definitely all different because why would they be the same?

That would make sense. there’s whole businesses centered around just ripping these documents, doing the OCRE, whatever. It’s one thing if it’s a table. And this kind of goes to the facts that Bloomberg stuff too. If it’s a table and you’re just like, I always want sell one, column one, row one, give me the number every time. Not super complicated, not a lot of assumptions that need to be made. And I think assumptions is one of the big things I think about when I think about LLMs and probabilistic patterns and things like that. And I can give you my convention there, but the number of assumptions it needs to make. Also relates to how much context you give it, how clearly you can describe the things it needs to do. So my usual grid of this is on one side it’s the number of decisions that you’d need to make. And then the other side is how much information you’ve given it, That’s any process.

It’s straight up any process. it’s for a human or a machine or anything at all. I could say, Shane, go make me a cake. I’ve given you no information. You have to make shit loads of assumption. You could make a cake out of mud and theoretically you’ve delivered, you’ve given me a cake, Or you could have made me a Lego cake for all I care.

That will also suffice, But that doesn’t necessarily meet what I have for expectations. So again long-winded piece here, but. If we did something more complex from a document processing perspective, A, hey, give me the revenue and the revenue’s in the cell, but then there’s four adjustments in footnotes and 12 other little things that you need to take into consideration. that’s how it gets complicated real fast. And we know in financial statements, this happens all the time. Like accounting for a lot of people seems like it’s a very route thing, and it is actually way more creative than you realize. So yeah, that’s where this stuff gets creative.

So to my process and doing things like this I always start small tasks. I always try to automate it if I can, if I’m comfortable with the security, et cetera. I always try. I have to start there to understand the bounds of what can be done or not done. And sometimes it’s process architecture to repeat that, or sometimes it’s how much information, am I clearly articulating the instructions, which is prompt engineering for lack of a better term, which is for humans, just fucking communication, which is always comical to me. I think that there’s no balance in some respect. You should always be trying to see what it can do again, I don’t think we’ve fully adapted to understanding I can use this every day. And that’s why I think it’s helpful for a lot of us to think of them as humans because it’s just oh, if I had an assistant, you’d know instantly what you’d have it do short of pick up my laundry, which it can’t do.

Shane: I think there’s there’s an interesting kind of thread in there that I’ve been thinking about, , and I’ll just unpick it. When we built our data platform, because we’ve been building data platforms for years as consultants, there were a bunch of core patterns that we knew were valuable.

And because we pay for the cloud infrastructure and cost, not our customer, we are hyperfocused on cost of that Google Cloud stuff, because it’s our money. We log everything. . Every piece of code that runs, we log the code that was run, how long it took you, we have this basically big piece of logging where we can go back and ask questions.

You, oh, are we seeing a spike on the service? Which customer you or customers is it one customer? Is it a volume problem? Is it a seasonal thing? Is it across all customers and Google are changing their pricing model, which they do on a regular basis. And so that’s just baked into our DNA. Yeah. Log the shit out of everything.

‘cause at some stage we’re gonna have to go and ask a question of those logs and we need that data. When we started moving into, AIing with our agent 80 we logged some stuff, but not everything. And as we saw our partners start to use her for really interesting use cases, they started saying, here’s some source data.

What kind of data model should I start modeling out? ‘cause we haven’t seen it. They have a piece of data and they wanna transform it. And so they’re saying, what we call transformations, we call ‘em change rules. What should the change rule look like? Talk me through how to create it.

And we just we saw those questions happening ‘cause we were logging the questions and, we started doing more context engineering to give her better access to things that gave her better answers. And what we didn’t do was when we moved to the, and air quotes here, reasoning models.

We didn’t ask her to log the reasoning path

Every time we asked her a question ourselves when we were testing something, we would ask a second question strike away of, how did you get that? Because we wanna understand where she’s grabbing the context, the prompt from. ‘cause that’s what we wanted to tweak.

And what was interesting is, our principle was log everything up, the kazoo, and yet we move into this AI world and we didn’t do it. And it’s and it’s of course once we saw. Once we saw our partners asking questions and we’re like, how the hell did she get that answer?

‘cause it’s not the one we wanted her to have. And then we ask her the same question and we get a completely different answer. We’re like, okay. And so then what do we do? We just put, into the prompt or into the framework, effectively log the path for every question you answer. And now we have a richness.

So that’s the first thing is it’s really weird how as data professionals, we have this baked in principles and patterns for our entire life. And then as soon as we move into this AI world, somehow we forget what we always do. The second point’s around complexity. And so one of the things I do when I’m coaching teams is I will ask them to draw me a map.

Draw me a map of your architecture, draw me a map of your workflow, draw me a map of your data sources. Like just draw me maps, Because I, I’m a visual person. And essentially what you say about, giving an L-L-E-M-A layout, a map, and distance between things similarity or clustering of things.

They are visual indicators as humans, we’re really good at using.

Shane: And so when I’m working with teams, the reason I want a map is the number of nodes and links. The number of boxes. The size of the map will gimme an instant identification or understanding of complexity. You have 115 source systems there that are going through 5,000 DBT pipelines.

I’m gonna go, that is a complex problem. You show me your team structure and it’s got, four layers of teams all handing off to each other and they’re in pods and squads and there’s 150 of them. You’ve got a complex business organization and team topology.

And so what’s interesting, because I was just thinking about as you’re talking about it, is if I take those reasoning paths and I basically do some simple statistics And I cluster two things, how many steps did it take that will infer the complexity of the context it’s trying to use in the task it’s trying to do.

And the second one is clustering around reusable paths where it’s constantly doing the same thing. Means that is almost a deterministic behavior, Because it’s constantly going through the same path. Where we see an edge case, an outlier, where it’s gone through a completely different path, we are like, Ooh, is that because, different question.

You just went and hallucinated for some weird ass reason. Or, yeah, there’s something interesting there because it’s different and we know different has value, which comes back to one of the things around eval, So there’s lots of work and it’s a new hot thing in the market is how do I eval my,

Yeah.

We used to call it tests, right? And, we know what data people like testing go back to my point of principles and patterns that we apply for our data work every day. And then in the AI world, we don’t, let’s talk about the ones we never apply. And now you get this whole idea of judging, So the idea of, if I asked the LLM the same question four times, and then I go and determine whether the answers are similar, and if they are the same or very close, then I should have more trust in the deterministic capability of that answer.

And that’s a presumably, I haven’t actually bothered to go and see any research papers to say if that’s true or not.

But is that what you do? Do you tend to use that as an eval process when you are doing all this work to apply AI to reduce your effort?

JT: Yeah. I always try and set up test harnesses of whatever kind, and I put evals in that same bucket. I agree. And, in. Our book club, We’re reading AI Engineering by Chip, which is a great book, talking all about the different evaluation methods and types, et cetera. I agree with the fact that I think this is a under invested area. I think it is a extraordinarily important area. And I equate it to testing in code, I think that there’s, a ton of code out there that isn’t tested for whatever ridiculous reason, And it’s always, people wanna move fast.

There’s businesses, blah, blah, blah. But, even if that means ad hoc testing, which is what you’re noting right now, run it a couple times and see the answer, that’s better than nothing. I’ve done a variety of methods now. I do LLM as a judge. I am still back and forth on this. So short of this, if you’re unfamiliar for anybody else it, it’s effectively, kinda like an adversarial, I have a system that generates something and then I have another LLM that more or less evaluates it.

I’ve done it with different LLMs evaluating others. So I might have Gemini as my model and I’ll use Claude as my evaluator or multiple evaluators, things like that. Or have it asked different questions from an evaluation standpoint, I’ve done that a variety of different ways.

That’s been very useful. I think anything where you can run your tests. At scale. Scale might be, that’s a very overloaded term. A any, anything where you can run a lot of tests, not spot tests, A lot of tests and a lot of extreme tests, I always tell people the QA joke about the bar, you know that joke, right?

Shane: I may do, but tell it in

JT: I’ll tell it anyways. I’m gonna butcher it. But the joke goes something like, somebody builds a bar, qa tester tests the bar orders one beer order, 99 beers, order a million beers, everything works fine. First guy in the door says, where’s the bathroom bar explodes? Great joke. Very appropriate in this circumstance, right? Of you don’t know what people are gonna ask. And I understand that large language models obviously are an NLP thing. It works on natural language, blah, blah, blah, blah. There’s many things in that case that are open-ended, so to say. And I think that the chat paradigm, especially as a UX paradigm, introduces a wild world of open-endedness, That, and anything can happen, And I talk to people that are building, again, AI products, and I’m like, do you want me to come to your product and ask you what my favorite color is? Because what what’s your thing gonna do then? You may have built this wonderful chat bot for finance or something, and I’m gonna walk up to it and be like, how do I make a chocolate souffle? And it might gave me a wrong answer. I might be like, this AI is terrible. I walked up to my finance AI and asked it where to drive to for lunch and it didn’t work. I was like no shit, but there’s a piece of that. I was just like, it’s not intended to work. So the open-endedness is pretty wild. But I do appreciate, there’s a bit of, this was just like almost chaos engineering, which is just I just wanna let it like just blast it with like random stuff. I also think that, having a prebuilt dataset, you should have some tests almost like unit tests to some degree. Ask it a question, you should get an answer. Then the next problem to your point is how do I evaluate whether the answer’s correct or not? And that, that is hard in and of itself. But there are conventions, ways you look for certain keywords, values, things like that. So I do think that evaluation’s massively important. It’s very easy to spot check a couple questions and just be like, yeah, it’s good. Move on with your life. And then you’re handing people free cars because they fucked with your chat bot, So it’s massively important, And I think that the more we can in a manner I speaking, beat the shit out of the machine and like literally test it to the nth degree. Even if you are using a language model, I think that’s helpful because the language model’s gonna come up with shit you probably didn’t even think of, like jack the temperature up and just tell it, ask random questions and make sure it doesn’t ask the same question twice through all I care and then you, this is our make checker a little bit can go review and say, Hey, this make any fucking sense. Or did it just spit out random garbage? I think all that’s super important. Like evaluation I think is very understated right now.

I think people are catching on a little bit, but. You said it before it’s very comical right now that we’ve got this new toy and everybody just forgets who the fuck they are and where they are, and they’re just like, yeah, cool. Let’s do it. You’re just you’re,

Yeah. You’re a seasoned professional.

Shane: Ah, And an organization. I was talking to somebody the other day and they’re in a large organization where security is key. And then they were saying that their cloud provider, somehow the LLM part of the platform got turned on for the whole organization.

JT: Ooh, fun.

Shane: Wow. And so it’s interesting how this AI thing seems to change, behavior.

People, you and again,

JT: that case might be a mistake, just like a human error.

Shane: yeah, maybe. But you do see, organizations that care about security and governance and privacy, and then you see people in those organizations grabbing things and putting them in their personal LLM. cause it’s so easy now to take a screenshot, and yes, they’re doing the wrong thing, but it’s amazing how human behavior is so different. when we talk about evals, we’ve gotta go back to complexity. Let’s just go back to data. If I have a piece of data and I have a piece of code and I have a, an assumption or an assertion I can define what the assertion is.

I can run that code against that data and the data doesn’t change, the code doesn’t change, and it can tell me whether that assertion is right or wrong. That’s three moving parts in that test suite. Why we don’t do that a lot really intrigues me. Now let’s talk about that within Gen ai.

Oh, actually no hold on. I’ve got. The data or the thing that I’m using, right? The input, PDF piece of data, I’ve got the question that I ask it, which is effectively the code to a degree and I’ve got my answer, my assertion that I expect. Ah, but actually I’ve got an LLM model, right? Which may or may not have been updated by the vendor without me knowing about it.

Ah, I’ve got a prompt. I’ve got a piece of text that’s actually embedded in that process that may or may not have changed or be interpreted differently. Ah, I’ve got rag or context, I’m pushing at some other stuff. That may or may not have changed. Ah, the PDF’s exactly the same except the dollar value for the invoice moved down 25 pixels.

Now that’s not gonna make a difference or does it? This is where we get to is that actually now if you do nodes and links for the process, we have lots more of them. And therefore, the complexity of what we’re testing the things that can change is massive. And talking about change again, one of the human natures I’ve found is once I start using a model or a tool, I get stuck.

I use chat gpt a lot for writing, because that’s what I started out with. I use perplexity for searching now. Over Google. So I perplexity. Now I don’t Google. We use Gemini for our platform because we’re bound to the Google Cloud. I use Claude a little bit for MCP testing, but I don’t use it a lot because I don’t code and I’m sitting there going, I can’t remember the last time I actually tried to decide when I would work out whether there are better models for what I want to do.

For the thing that I use chat GPT for. So how do you deal with that? Given the models are changing all the time and that the models are, tend to be good at specific tasks how often do you reevaluate the tool or model that you are using in the work that you do?

JT: not as much as I think I should. But I evaluate the new ones as they come out. So , when GPT five came out, like I reactivated my open AI subscription, I really don’t like open ai. I don’t know what it is. I maybe they, I just like, feel like they’re like evil empire or something.

I, like everybody else started using their products when they came to market and, even before chat days. And I’m not gonna be that guy that’s just oh, I’ve been doing this before. But I used that stuff before and it was interesting and I was very curious about it, especially given like the work that I do. when, Chachi PT came out, I was definitely all over it and I was very fond of it. So I will tell you that I very often use for understanding information. I use Gemini, I appreciate that one. I am a Claude fucking junkie when it comes especially to coding, And I’m a heavy cursor user, like very heavy cursor user. And I will tell you my favorite thing that has come out period, that no offense to you, Shane, but I have definitely done some work while we’ve been talking, right? And this is my favorite thing. I have my ticketing system wired up to background agents or cursor.

So like I write. Reasonably verbose tickets that explain exactly what I wanted to do. And for context, like the scope of these tickets is like, Hey, you were taking in parameters one, two, and three. I don’t want that. I want it as one parameter that looks like this. And then I want you to do this with that. That’s the scope of tickets that I’m writing because I want to be in control of it. And it’s like a micromanagement approach. I write the ticket, I say Go and it writes it. And I just keep on with my day. So I could be like walking my kid or my dog or somewhere and I’ll just fire fucking tickets off.

I’ll be working all the time. It’s amazing. That’s my favorite feature by like a absolute mile and a half. And I love Claude 4.5. I think it’s amazing. And the code quality’s phenomenal and I’m probably paying them a disgusting amount of money. But it’s, I think it’s totally worth it right now because I can move epically fast and multitask.

so Gemini for information, Claude for code open AI for nothing unless I like, just want an alternative opinion. And I definitely consider them all like different people to some degree. I very much think of them like people, they all have their different quirks .

Some things are good, some things are bad. Some things are like, especially from a code perspective, some of the models are more overeager than others. Some of them wanna try and cover more edge cases than others. And I, sometimes I’m just like, no, just fucking do what I told you to do. I don’t need you to do 20 other things.