Join Shane Gibson as he chats with Marco Wobben about the patterns within Fact-based modeling.

Listen

Listen on all good podcast hosts or over at:

https://podcast.agiledata.io/e/fact-based-modelling-patterns-with-marco-wobben-episode-81/

Subscribe: Apple Podcast | Spotify | Google Podcast | Amazon Audible | TuneIn | iHeartRadio | PlayerFM | Listen Notes | Podchaser | Deezer | Podcast Addict |

You can get in touch with Marco via LinkedIn or over at https://casetalk.com

Tired of vague data requests and endless requirement meetings? The Information Product Canvas helps you get clarity in 30 minutes or less?

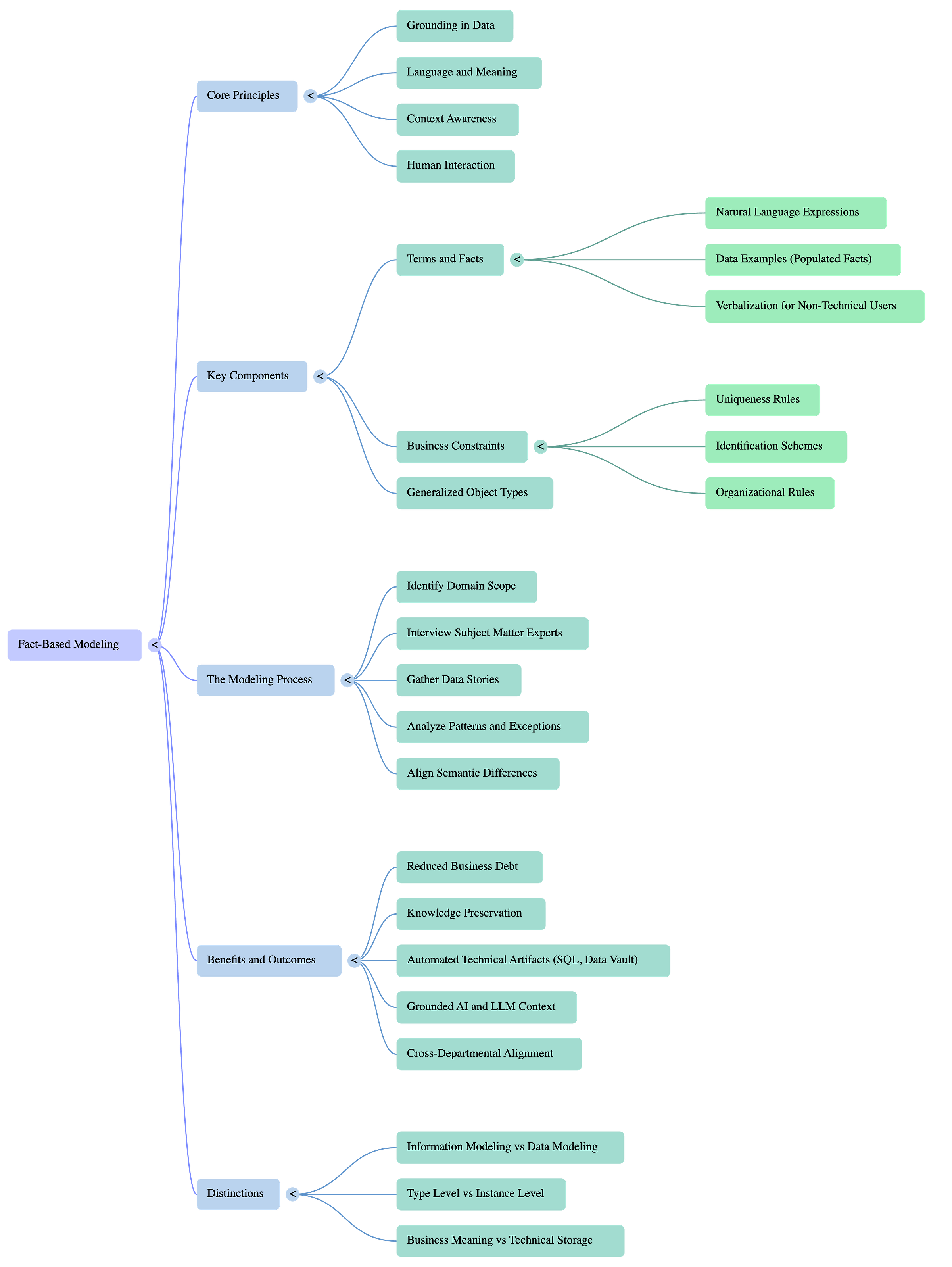

Google NotebookLM Mindmap

Google NoteBookLM Briefing

Executive Summary

This document synthesizes key insights from a discussion between Shane Gibson and Marco Wobben regarding Fact-Based Modeling —also known as Fact-Oriented Modeling. The central premise is that modern data modeling has become a “lost art,” leading to significant “business debt” where organizations lose the context and meaning behind their data due to silos and rapid staff turnover.

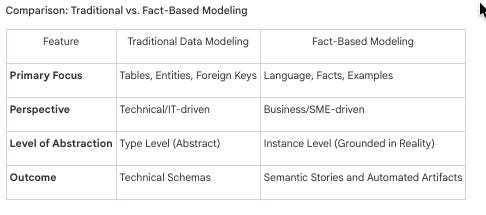

The core solution presented is Fact-Based Modeling, a methodology that grounds abstract technical requirements in “administrative reality” by combining linguistic terms with actual data examples. By focusing on how stakeholders communicate (Information Modeling) rather than just how systems store data (Data Modeling), Fact-Based Modeling allows organizations to bridge the gap between business subject matter experts (SMEs) and technical implementations. This approach not only ensures more accurate system design but also provides the necessary semantic grounding for emerging technologies like Large Language Models (LLMs).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Crisis of Lost Context: Technical and Business Debt

The current state of data management is characterized by a widening gap between what is stored in systems and what those records mean to the business.

Evaporation of Knowledge: Senior experts with decades of organizational history are retiring or leaving, and the average job tenure (four to six years) is too short to maintain deep context.

Business Debt: This is the cumulative loss of meaning within an organization. When systems are built without documenting the “story” behind the data, the original business intent is lost, leaving IT to guess the context of legacy records.

The Context Gap: Technical optimization (how data is stored) often overrides business representation (how data is used). This leads to “tribal wars” where different departments use the same terms (e.g., “inventory” or “customer”) to mean entirely different things based on their specific departmental needs.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Defining Fact-Based Modeling

Fact-Based Modeling is a methodology developed to capture domain knowledge by focusing on “facts”—statements about the business that are agreed upon as true within a specific context.

Core Components of the Fact-Based Modeling Approach

Grounding in Examples: Unlike traditional modeling that looks at abstract entities and attributes, Fact-Based Modeling uses “data by example.” Instead of discussing a “Customer” entity, a modeler uses a statement like: “Customer 123 buys Product XYZ.”

Binding Term and Fact: By combining the linguistic term with a concrete fact, modelers can identify misalignments quickly. For instance, seeing that one system identifies a customer by an email and another by a numeric ID reveals a transformation problem that abstract modeling might miss.

Information Modeling vs. Data Modeling:

Information Modeling: Focuses on how humans communicate about data to reach alignment.

Data Modeling: Focuses on technical storage, structures, and optimization.

The Distinction: Information modeling is the “primary citizen,” while technical artifacts (SQL, schemas) are secondary outputs derived from it.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Methodology: The Process of Fact-Based Modeling

Fact-Based Modeling follows a specific logical flow to ensure that complexity is simplified without losing essential nuances.

Scope the Domain: Identify the specific problem area (e.g., Sales, Emergency Room, Tax).

Gather Data Stories: Interview SMEs to collect verbalizations of how they describe their work.

Identify Business Constraints: Use interactive questioning to find the “rules” of the data. (e.g., “Can a citizen be registered in more than one municipality at once?”)

Identify Exceptions: Use the data examples to flush out the “edge cases” that SMEs often forget until they see a specific record.

Alignment through Generalized Objects: When different departments use different identifiers for the same concept (e.g., Name vs. Email), Fact-Based Modeling uses “generalized object types” to link these different views into a unified communication framework.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Strategic Value and Modern Application

1. Automation and Efficiency

Fact-Based Modeling allows for a “context-first” implementation. Because the model is rich in semantics and constraints, tools can automatically generate:

SQL for database creation.

Data Vault or normalized models.

Database views that represent the original user stories.

Test data derived directly from the interviews.

2. Grounding AI and LLMs

LLMs are proficient at generating “fabricated stories” but lack organizational context. Fact-Based Modeling provides the “ground truth” needed to keep AI outputs accurate. By feeding an LLM the terms, definitions, facts, and business constraints from a fact-based model, the AI can perform tasks with a much higher degree of reliability.

3. Avoiding the “Generic Model” Trap

The document highlights the failure of massive, pre-built industry models (e.g., the IBM Banking Model). These models often fail because organizations do not know their own “edge” or specific context. Fact-Based Modeling allows a company to capture its unique business logic rather than trying to fit into a generic template that ignores their specific reality.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Notable Insights and Quotes

On Complexity and Simplicity: “If the end product is presented and everybody goes: ‘Wow, is this it? Did it really take you that long... I could have done this,’ then I succeeded in making something very complicated very simple to understand.” — Marco Wobben.

On the collaborative nature of solving data ambiguity: “It is somehow a team effort to slay this beast of miscommunication until everybody agrees and understands each other. ... It’s all about, working together and trying to fight it. What are we not seeing? What are we missing? How do we tackle this? And a lot of that is just human interaction.” — Marco Wobben.

On the Definition of a Fact: “A fact is a piece of data that’s physically represented somewhere... I can point to it. It has been created. I’m not inferring it. It is something that is factually there.” — Shane Gibson.

On Party Entity Data Models: “The most expensive part of our systems is the humans and [understanding] that context... as soon as you design a system with ‘thing as a thing’ and that context lives nowhere else, I now have to spend a massive amount of expensive time trying to understand what the hell [it is].” — Shane Gibson.

On the concept of “business debt” created by rapid technological change: “This is the paradox where business wants to have changed faster. And it ruined the party by saying, we can deliver faster with this new latest tech, but neither party realized what they were losing along the way. So it’s technical debt, it’s business debt.” — Marco Wobben.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Conclusion

Fact-Based Modeling serves as a bridge between the human understanding of business processes and the technical requirements of data storage. By prioritizing the “authentic story” of the business and grounding it in real-world data examples, organizations can mitigate the risks of technical and business debt, ensuring that their data remains a usable, understood asset even as technology and personnel change.

Tired of vague data requests and endless requirement meetings? The Information Product Canvas helps you get clarity in 30 minutes or less?

Transcript

Shane: Welcome to the Agile Data Podcast. I’m Shane Gibson.

Marco: And I’m Marco Wobben.

Shane: Hey, Marco. Thank you for coming on the show. Today we’re gonna talk about a thing called fact-based modeling, but before we do that, why don’t you give the audience a bit of background about yourself?

Marco: Ah, yes. Thank you. Thanks for having me. Yeah, background a lot of background there. I’ve been around a few decades. I first fell in love with computers when I was still in secondary school. That got me hooked when somebody showed me the break key on a keyboard and we could stop games mid play, change the code and resume.

And that was like, oh, this is magic. I need to figure out how to make this my toolbox. And I enjoyed making software, hacking software working with computers ever since. And. From getting a job onboarding people on Microsoft Windows and Office. Back in the day, I decided to just chase my own career, quit the job and started doing entrepreneur work, made custom software from design to end product for a number of startups. And then somewhere early two thousands, a professor knocked on our door and said, we have this source code of a modeling tool. And the kids that graduated on it, with, they took a different path and we need somebody to maintain it. And ever since early 2000, I’ve been working on fact-based modeling that I had to learn from the inside out.

So that’s where I am now. I’m being considered the expert currently. ‘Cause a lot of professors retired and the young people haven’t caught on for it yet, just and here I am talking about fact-based modeling or fact oriented modeling, if you will.

Shane: Yeah, it’s interesting. We before we started, we talked briefly about the fact that data modeling’s become a lost art. And actually, I think it’s coming back now with all the AI focus, it seems that data modeling is a term I’m seeing used a lot. But, if you think about your career path, that idea that you could start out with games as a way of introducing yourself to, to computers in the early days.

I was like, you I started out. We had a couple of computers at school. The old I think they went green. I think they were amber screens back then. And yeah, again, I got hooked by the games. And I wondered whether that’s the thing that’s been missing is gamifying data modeling.

Like actually making it exciting is, it’s probably the missing thing, right? Is if there was a game that you just happened to date, a model when you did it. Maybe that’s what we needed to make what we do sticky with with people that are coming up in their career.

Marco: that’s an interesting take on it. it’s interesting looking at my users, I’ve been maintaining this information modeling tool for years now, is that there seems to be more. Interest from people that are curious and like doing things right and talk about things. And this is, I can see that in, in a lot of gaming communities where, you know, in the old days it was like you play your game single player with this computer, right?

But gamification nowadays is so much more you can team up and you none of that stuff was there in the early years. Even graphics were not there yet. The communication aspects right nowadays is more and more prevalent and important and it’s. If you look back, what data modeling really is to get the technical requirements of what people actually needed the computer to do in store and how to manage it.

Seeing that come back a little I dunno if gamification would help, but there’s definitely more openness to let’s talk about it. And you can see it a little bit in the agile phenomena where there’s a lot of standups stakeholders, product owners, and everybody starts talking and communicating with each other.

So that’s definitely on the rise. I’ve seen a few data modeling efforts that actually try to gamify it and it’s like a, they have this data modeling tool and it has flashing text and animated tables and, I’m not sure if that’s really the end goal, but I can see how it might help.

Shane: Yeah. I was thinking more about gamification as in the adrenaline rush when you are successful in solving a problem not the flashing things. Because earlier in my career, I worked for a software startup in the accounting space called X. One of the reasons that they became successful was they had this gamification of bank reconciliation.

So pretty much you had bank transactions on the left and your invoices and all that on the right. And whenever a transaction came up on your bank statement, you pretty much dragged it and matched it to the right. And then that road disappeared and it was a very simple gamification process.

But there’s this adrenaline rush going in and seeing your bank rec with 50 transactions you haven’t reconciled, and just going bing, bang Bosch, and it becomes clear. And, I don’t, it didn’t have confetti. Actually that was one of the big arguments at the time was should it have confetti con?

Marco: more like a Tetris road disappearing from your screen.

Shane: Yeah. Yeah, exactly. And so you sit there going, maybe that’s it. So as I think about it more, when I’m conceptually modeling the adrenaline rush is when I create a map that I can show to a stakeholder and they just nod and go, yeah, that’s business reality. I get it. Yeah. That’s how we work.

When I logically model, it’s this idea of yeah, I can take that conceptual model and I can slam it into the modeling Pattern that I use and it makes sense. And then when I take that logical model and I make a physical model and the cloud database actually takes it and I can actually query it fast and it doesn’t cost me a fortune, and any question that I get asked can be answered with that data.

There’s that adrenaline rush, right? That gamification of each of those steps adding value to my life or somebody else’s. I don’t dunno, I just, I haven’t thought about it that way until you mentioned that you started out hacking games.

Marco: That is, it definitely is true for me because, as I add features that support user functionality and all that, and it’s like there’s definitely a rush when I see people use it and they go oh, this is handy. This is practical. This, makes my work easier. Then I get the adrenaline rush. Definitely on the modeling part itself. It usually goes through long cycles of deep talks about the subject matter at hand, which, there’s definitely an adrenaline rush, but not necessarily always the good ones. As a, as an example that I used a lot and some other authors put it in their book too, is I had a long interview with the subject matter expert and it took us about two hours to figure out one requirement, and there was a lot of talk on the type level that created confusion because, yeah, what is a customer really? So I have to get through that. And in the end there was a little bit of an euphoria, which is, the adrenaline in rush, if you will, where we finally nailed it. The subject matter expert re replied, somewhat baffled and in disbelief, and he says, I had no idea my work was that complicated. And then being able to write it down in a way that everybody suddenly understands. That’s definitely a moment of adrenaline and rush, if you will. It takes two hours of hard work. It takes a lot of interviews, a lot of digging. And then finally when you reach that point, and it’s like one of, I remember a quote in a book I forgot which one it was, but I the quote really spoke to me and he this man was speaking about information modeling on a data modeling level.

And he said if the end product is presented and everybody goes. Wow, is this it? Did it really take you that long and work so hard to just present this? I could have done this, and then his reply was then I succeeded in making something very complicated. Very simple to understand.

Shane: And that’s the key is to take that complexity and describe it in a simple way where everybody nods and either agrees or disagrees. I remember one where we literally spent three months with an organization trying to get the definition of active subscription. And the problem was we had three business units.

Effectively three domains that all had different definitions, but couldn’t agree. They actually had different definitions. It wasn’t around the model itself, it was around the plain language description of that term where either we added a term in front of it, marketing, active subscription, finance, active description.

So we were clear they two different definitions or they actually agreed active description was described in this way. And that human engagement was where the time was spent not creating a map with nodes and links on it. Not creating the database, but without actually getting to a stage that we ever agreed or disagreed with that term.

There was minimal value carrying on because we would present a number that people don’t agree with because the definition’s wrong, not the number.

Marco: in the years of information modeling that I, I call it information modeling, but it’s really just a fact-based modeling underneath as well. But I’ve encountered so many synonyms or harmoniums or it’s just, people just completely get confused and it becomes almost like a battle.

But here’s the thing, and I think you explained that as well. It is somehow a team effort to slay this beast of miscommunication until everybody agrees and understands each other. I just recently started watching the latest series on Stranger Things that it’s we have to team up to fight this monster from the underworld, which is, we can’t see it. We know it’s there. And it’s like, how do you fight it? And and it’s all about, working together and trying to figure it out. What are we not seeing? What are we missing? How do we tackle this? And a lot of that is just human interaction.

Shane: And finding ways of taking that expertise that we have that ability to take complexity in a business organization and try and create a map that has simplicity that we can all share. That is a skill, And it’s how do we take other people on the journey without going into a room for six months on our own or creating really complex ERD diagrams with many to many crow’s feet that, few people understand, And terminology is really important. And so it’s interesting that you talk about information modeling and then you also talk about fact-based modeling. ‘cause as soon as I heard of fact-based modeling, I naturally go to dimensional modeling and star schemas because that is where I first heard a definition of the term fact.

And my understanding is you are talking about information modeling rather than anything to do with dimensional or star schemas. Is that correct?

Marco: Yes. That’s funny ‘cause your first take on the word fact is how I met my wife at a data modeling conference in Portland in the USA. She was like, oh, fact-based modeling I’m doing something with data warehousing. I should go to that class to listen what this man has to say.

And it was just not the same fact. So even there, even in it, we have confusion of words, but the word fact really boils down to something that is maybe a little older even where database records really store facts as they happen in our administrative reality as I call it nowadays.

Because there’s a lot of the single point of truth. We need to get the truth out there, the reality and all of those things. But there’s something seriously flawed with that, is that we all perceive from our own bias and subjective reality, the world out there. So there is no such thing as truth. But when you store data and you consider that to be true in your world, then you can state that as effect. Effect as in, I’m writing this down and me and my colleagues agree on it. And so that’s where the terminology came from. Nowadays we trying to figure out, maybe we should call those claims instead because we all say something and we all think it’s true.

And sometimes, especially in data warehousing you collect data from different source systems. Yeah, but you can’t just say that they all state facts because some might be alternate facts. So let’s put it as all the source systems claim a certain statement about this is what happened.

Shane: it’s interesting, ‘cause we’re talking again beforehand about how we’ve both been in the domain for quite a while, but we’ve never really crossed paths. And I’ve heard your name a lot, but I’ve never really read a lot of your stuff. And one of the things I did do, I had to train a new team moving to the data space.

And so I was trying to describe the difference between facts, measures, and metrics. And what he ended up coming up with is a language definitions that I used and the definition I used was a fact is a piece of data that’s physically represented somewhere. So if I go into a database and I see a number.

That is a fact. If I go into a spreadsheet and I see a number or a piece of text, that is a fact because I can prove it existed. I can say, that factually it’s there. I can point to it. It has been created. I’m not inferring it. It is something that is factually there for me. And that’s kinda why I use fact.

And the reason I raised information modeling versus dimensional modeling is ‘cause as soon as I use that term fact, anybody in the data domain goes, oh, you’re talking about a fact table. And I’m like, no. And then for me, I defined, measure as a formula, some of this, that kind of thing.

And then a metric is a complex formula. So this over this based on that at this point in time. And so for me, I didn’t mind whether people disagreed with my definitions as long as they gave me a different definition. But that’s the three terms that I used that seemed to get clarity and understanding when I was talking to people who weren’t data experts.

So yeah, I go back to the true definition of that term. Fact is not a fact table and a dimensional model. And, maybe yeah, should we move to claim or should we just bring back the true definition of that term, that’s one of the problems we have in our domain is we have what we call pedantic semantic arguments about the the most non-interesting things for.

Marco: We are not gonna solve that because there’s so much when I do actually information modeling and we can come up with the word, I’ve used it in, in, in different environments, but we can all agree upon what the definition is for the word inventory. It’s the amount of things that we have and offer certain article, but then you go into different departments.

Sale comes up with three because they already sold a few. Purchasing says, we have eight because they already ordered a few. And then you go into the warehouse and the guy goes but I only have one on the shelf. The, what the hell is going on? No, even though everybody agrees they have different data. And as soon as you, you and I would speak about facts, then, I could say that the customer buys a product and we agree and we call that a fact, but it has nothing to do with the data at all. So the word fact itself is like inventory, is location is like customers that you can apply it to anything and it doesn’t mean anything. So getting too hung up on it. Is very tricky because then you will start tribal wars because no. This is what the definition for a fact is. But the reality is that the word fact the linguistical part of it, the term of it is used in different contexts. So if you wanna use it within your dimensional world, it’s fine. I’m not gonna argue with that. Is similar to calling something red, we will find it in different environments. I’m looking at a book that has a red cover. You look at the fire truck is also red. It’s, oh, we’re all good.

Shane: Unless you’re in a country where the firetrucks green. And yeah, it’s interesting ‘cause Remco Broekmans talks about the example he has of definition of a bed in a hospital. And where one group basically said, it is the metal frame that the patient sleeps on. And another part of the organization said, nah, hold on.

It’s the room where the patient’s located. And so if I looked at the data, I would see one was probably two meters by two and a half meters and the other one was probably five meters by five meters. And then I could say the fact that this beard is five meters by five meters and has no wheels confuses me because I’d expect it to be two by three with wheels.

Maybe that data’s gonna gimme a hint that the definitions are different. So getting into that. can you just gimme a helicopter view of how fact-based modeling works.

Marco: You already gave me some beautiful examples is that to distinguish the things. You also have to look at the data and what I see happening in the data modeling space is usually. The data is not that relevant. We’re all looking at tables, entities, classes and what kind of attributes they have, what columns need to go in and what are the relationships or foreign keys and all.

So there’s a lot of technical views on it, and some of it may be guided by the data at hand. But the data itself is a secondary citizen. And as I just stated with the example of inventory, is it’s only by looking at the data that you start realizing, wait a minute, we’re all calling this inventory, but we’re seeing different things.

So there must be a distinction. And instead of having, this, I call it these tribal wars, these linguistical fights about no, that’s not what I said. This is what it means. And all of that. I call that. Type level arguments, type level discussions. It’s abstract in a way. So what factory ended modeling does is two things, is first, how do I talk about my data? And I use the data in the expressions, so I’m grounding it. I’m not talking about customer buys product. I’m saying customer with customer number 1, 2, 3 buys the product X, Y, z. Where both 1, 2, 3, and x, YZ is actual data, is real examples to ground the discussion.

Because, if I use inventory and I don’t specify that, I look at it in a certain way by giving the data, we will not discover that we might have a difference of perception there. So why the factor oriented modeling or fact-based modeling is that really we need to figure out how. I talk about it, how you talk about it and how we can talk about it and ground it with actual facts, this actual data it’s not enough to say the customer buys the product because you and I would agree, but it’s only by giving the actual data examples that we might start realizing, wait a minute, I have numbers to identify my customers, and you might have email addresses to identify your customers, so there’s something else going on. So it is really digging that one level deeper into it, and not letting that go because in the fact-based modeling, we keep tying the examples data with the language, with the fact types. So it’s always that package so that we can at any point, transform our information models into any kind of artifact, but still show the example data to accompany the definitions, to accompany the structures and to illustrate that this comes with a specific data use. And I think that’s the biggest difference from what you look at data modeling or dimensional modeling or data vault modeling is that it’s all on a type level and it’s usually geared towards how do we structure the storage of data. And it’s less about how do you and I figure out how we talk about the data and how do we quantify with data that we’re talking the same thing?

Shane: What I found interesting was so I’ve used the who does what Pattern a lot, And I think, I probably got it from Lawrence Coors Beam stuff. ‘cause that was some of the stuff I read earlier in my career. And I’ll often talk about customer orders, product from employee in store.

And then I’ve also used data by example a lot. And again, I can’t remember where I found that patent, but I found it valuable, so Bob purchased three scoops of chocolate ice cream from Jane at 1 0 6 High Street in Swindon. And what interests me about the fact-based modeling when I had a quick look at some of your presentations, is it seems like you are combining both those patterns.

So you are combining both the term and the fact into that data story. So you are saying, customer Bob purchased product, chocolate, ice cream from employee Jane at store 1 0 6 High Street.

Is that what you’re doing? You are combining the term and the fact together to give much more context around that business reality to then help you in the rest of the work.

Marco: yeah, definitely. It’s very much that approach and of course tools give you different functions to, to do it in a different way. But the theory that was even developed in, mid seventies and continue to develop all the way up to the end of the nineties was really about how can we write it down in a way that non-technical people can actually read what it means.

And in the interviewing phase, in the workshops, in the explorative areas, is that, as I’ve given the examples earlier is that it’s not enough to just say, okay, we have a customer and we need a data system for that. It’s like we needed to also figure out how you talk about it.

And I think what is an increasingly more difficult problem is that where in the seventies, eighties, even nineties a lot of systems were built for a specific purpose, for a specific department, for a specific system that everybody knew the context of. So now if I’m doing a customer registration, then I’m just doing just that for my department within my group of employees.

And we all know the context. So everybody understands that if I put customer there, they all know what customer is. Now with the increase of it is that. It added a computer on every department, in every system, But they never integrated. So this is where data warehousing came in. But because it was very high context, implied the data warehousing, the BI team now had to figure out, okay, what if we pull the data?

What does it even mean? But we’re really trying to rediscover the context of where it is used. The human aspects of understanding need to be reverse engineered on top of the data structure. And this especially goes for what we’re currently seeing with all the LLMs. Yes, it can give great semantics or storylines, but does it really understand the context?

So this is another gap. And what the fact oriented modeling approaches is that we try to interview and capture the knowledge of the domain and subject matter experts. With all the context, with their language, with their examples and try to line that up with the data, the language and the meaning of some other department that uses a different system. And not just to be able to talk about that specific system, but to also align the communication across departments, across contexts. That’s really what got lost. If you have individual silos that you want to bring together into a data warehouse solution, that the missing piece is the original and authentic communication about their systems in the first place. And then the factor oriented approach allows those subject matter experts to talk about it in a way that they understand and can be verified by colleagues and can be transferred across. Context. And I think that’s the real added value that when systems were built within a specific context, the value of that was not really seen because it served the context.

Everybody knew that. where you see now an increasing in interest in, okay, we need to get back to our ontology, we need to get back to our semantics. We need to get back to meaning, we have to get back to information. So all of that was there and it’s still there if you don’t throw away the baby with the bath water.

Shane: I agree. I, we go through waves, so we see a wave right now outside the AI wave. We see a wave of bi me metric layers. This idea of having a layer where you can define a metric and then regardless of which system, the data’s coming from or you are hitting that same metric’s been applied.

And I go well, you know, years ago in the old BI tools we had end user layer or a universe. We’ve had that Pattern and then we lost it, and then we get it back. I’m also with you in terms of the way systems have evolved. We’ve gone from a mainframe where we had one system where there was a term called customer and there was one fact and that was it.

And then we went to client Server N Tier, and we ended up with seven. And then software as a service, 50 to a hundred. And with the AI wave now and Gen ai, we’re gonna see these one shot apps. We’re gonna see thousands of things that have created for one use case get stood up really quickly, and then probably disposed of.

And so this ability to have a language where regardless of the system and how many we have, we get shared context is really important.

And that example that you used, I just wanna come back to that because I hadn’t thought about it that way. So if I said customer orders, product. I have a thousand systems that involve a customer, an order, and a product.

I have absolutely no context whether they’re defining the same things the same way.

But if I use this data by example, if I say customer, Bob, ordered product, and then in another system I see customer bob@gmail.com ordered product, and in another system I see customer 1, 2, 3, ordered product, and in another system, customer A, B, C, ordered product.

What I know now based on Pattern recognition, is that I have a problem with the unique identifier of customer.

Like I can tell that in 10 seconds by seeing those four data examples and it’s something I know I need to solve.

Because to mash that all up, I need some form of conformity, right?

Some form of either shared identifier or a way of mapping it. And so I can see by this combining this term and this fact together, it gives me the richness to understand the problems I need to solve much quicker than any of the other techniques where they’re separated.

Marco: That’s true and it’s, you’re still some somewhat catching an optimal path because you already assumed in this example that all those systems had something called customer. And in one system it’s probably CST. Then you have to combine it with SAP, where it has X 3 0 4 as a table name and then you have a very abstract table called persons. So you can see where this is going because all of those systems, the storage and the structuring of the data in that system served only one purpose. Optimizing the IT part of it, the IT end product presented the data in a way that the business wants to work with it and wants to see it, but it doesn’t represent how it is stored. The storage and the management of the physical data is technically optimized. It is not with the business representation in mind necessarily. And this is what a lot of people in the data space have encountered too. It’s okay, now I have 200 source systems and I need to figure out what is what.

So is this email address, does that indeed correspond with my customer? In the other system where it’s identified with 1, 2, 3, is that even the same customer? Is it a customer in the first place? So there is so much not just technical debt for systems that are undocumented or not well documented or behind in documentation, but also a, what I increasingly call the business debt is that nobody knows what that meant to the business anymore. And this is the paradox where business wants to have changed faster. And it ruined the party by saying, we can deliver faster with this new latest tech, but neither party realized what they were losing along the way. So it’s technical debt, it’s business debt. In governments it’s even worse because there’s a massive gap between the legal articles made up by politicians full of compromises and loopholes to the actual systems used by government bodies.

And, now we changed the law. Which system did we need to change or vice versa? We’re looking at data here but we have no idea if we’re even allowed to have this data or even be able to look at it because we don’t know the legal articles with it. So everything in it scaled up in the past 30 years so quickly. It totally got outta control in a way where the next tool’s not gonna solve it. An LLM is wonderful, magical stuff, but it’s not gonna solve the real thinking issues. We can do data profiling because we were still not sure if we got the context right. We can do LLM, but we are still not sure if the relationships are correct. So there’s still that gap of knowledge that we lost and somehow need to reintroduce to make things really work.

Shane: And actually that’s interesting around that organizational context and losing that knowledge. Because if I think about it, if I was walking into a new organization and I wanted to understand the context of that organization, my natural technique was to find somebody who’d been there for a long time as a subject matter expert, that person that’d been there for 20 years because they’ve got the stories of how that context happened and why it happened.

And so moving to the uk I had to set up bank accounts. And so I went, and there’s a whole reason that I needed to do a UK domicile bank rather than one of the newer, easier to deal with banks. And so I went to one of the main banks, I created a personal bank account.

Took a while. All good. And then I went back to that. ‘cause now I’m a customer of being identified. In theory. Everything is easy. And I tried to create a business bank account and it forced me to create a new identity. I had to go through the whole identity process, even though I used the same email address, which was my form of identification, my identifier, I had to go and revalidate myself that I have a same address, same passport number.

And you sit back as a customer and you go, that’s just crazy bollocks. And then I talked to somebody that had worked for that bank, that subject matter expert who’d been there for a while. And they said, yeah, but you gotta understand that was two different banks, two different systems, and they haven’t been merged.

And therefore you may think you’ll be dealing with the same organization, but you’re not really. And I’m like, yeah, actually. Okay, that makes sense. Now why? Why did I not understand that working in data so often, but if we go back to that example of term, in fact, so yes, if the term changes, so now I see a customer and I see person and I see prospect and I see X 2 0 3.

If the fact is the same, if every one of those is customer Bob at Gmail X 2 0 3, Bob at Gmail, prospect Bob at Gmail, again, I’m getting more context, I’m not getting an answer, but I’m getting more information that can help me understand a problem to be solved. And as we know with data, there’s so many problems to be solved.

It’s such a complex space. When we hit reality of organizations, the way they work, the terms they use, the systems they use, the way they create and store data. But this idea of binding term and facts. Gives me some more hints because now I can say they’re all the same email address, are they the same term?

And then somebody will say actually no, when you see prospect and customer, it is a different rule and then somebody else will go. But you do know that they can change their email address whenever they feel like it. And you’re like, yep, seen that Pattern before. Okay, so it’s an identifier, it’s a unique identifier, but it’s not a consistent or persistent identifier.

There’s all these patterns and data that we know are gonna hit us, but by binding that term, in that fact, I get some hints at the beginning across multiple subject matter experts. So I can see real value in, in that part of the process early. And so talk me through that, You drop into a new organization.

You wanna start off with fact-based modeling. How do you do it? What do you actually do?

Marco: It’s a funny question. I, a lot of people ask me that, how do you start it? If you open up the books about this topic that either are written as a university. Proof of concept all the way to, self study. It always starts with gather your sources, figure out what is the domain about in the first place.

So there’s very much a almost top down approach where you go okay, we got sales, we’ve got production. so it’s the general area. You can’t just jump into the jungle and start describing all the little insects on the jungle floor.

It’s that’s not how it works. But usually there is a problem domain, there is an integration problem. and. So what needs to happen is that you need to be able to carve out some time with at least some business domain expert subject matter expert to sit down and say, okay what’s the issue here?

What do you, what are you doing? What does it do? And start writing it down. so far, not that much different from actual data modeling, if you will. But the distinction starts with the nitty gritty where you need to get things right. And it’s usually getting things right, not just to verify if you understood correctly, because that’s already a hard part as my two hour example earlier showed to, just get one line of requirements, correct. But that back and forth with language and examples is of great help in getting to actual understanding. But the major part is usually you need to work with a colleague that also needs to understand it. And with the current short-lived career jumps, if you will, is that you may find an expert, but he might be gone in four hours or as is happening currently as well. A lot of seniors that actually know the organization, they’re getting in a pension range and they just leaving the company. And what is left behind is usually short lived career steps, short lived managers that move on. There’s a lot of tempo where at the average job years is four to six years. So the knowledge actually evaporates while we’re looking at it, while we’re trying to document it. and that’s where the difference starts to rise between traditional data modeling that creates diagrams and type level schemas into a, if you compare that with factory and modeling, you have real user stories that you can, with a click of a mouse can pull up and you can read how it’s being used in language in the organization and how it’s being transferred to other departments. And I think that securing that knowledge, that semantic rich document, if you will that is something that I see that gets lost with the more traditional, more technical data modeling. It’s, yes, you have the traditional layers of conceptual, logical, physical. But still, there’s not really a story there. And the people that I talked with and explained this kind of stuff is that they all recognize what I’m describing and a lot of the architects and a lot of the data models will reply with, yeah, that’s what I do in my head. And then my question is, my obvious question is but does it leave your head, does it get written down somewhere so that if you leave, your colleague can take over? And then the answer is usually no. There might be a document somewhere, describes the use case, but that very quickly gets evaporated as well, because everybody starts looking at the artifacts and the technical schemas. So by having an environment where you tie it all together, that you cannot do one without the other. That was really the grounding for the discussions the proof of the pudding, if if you will. But it also gives you the anchors going forward to technical artifacts. So by capturing that from the domain experts, putting that in an information model and being able to generate technical artifacts, even SQL to generate database, it will still comment all that SQL with all the written language and examples. It will generate a database with test data that came from the interview in the first place. It will add database views representing the full user stories on top of the production data, representing the interview. So it really is that don’t throw it away, don’t throw it away. Keep it as long as possible so that everybody is able to understand and read what the actual data is and what it means and how it’s communicated.

Shane: that’s interesting because that is a form of context first implementation. And what I mean by that is with our product, we define the context first and then the technical implementation is hydrated. So I’ll create the context of a business rule, change rule, and then our system will hydrate that into physical tables and SQL transformations.

But that context that I create is the key thing we, we care about, right? That is our pet. The way we deploy it and run it is our cattle. And what we’re seeing in the new Gen ai, LLM world is that context is actually far more important for the LMS and the physical implementation of that context.

And then as I said, we’re I’m working with Juha Coer at the moment trying to write a book around how to concept model. And one of the things we came up with is one of the steps is define your domain scope. So like you said, find a subject matter expert who understands it.

The next one is get data stories. And then after that, identify events, then concepts, and then connections or relationships. And the key thing is, as you said, is when you talk to experts in this process, if they can articulate the steps they take, those steps are often common. They might use different terms, and they might do them in slightly different order in slightly different ways, but we all do it the same.

If we think about it consciously, it’s where we bring in patent templates, where we bring in artifacts that we use repeatably, that we get that repeatability, that ability for that context to be stored in a way that another person can use it.

So in my view, yes, it’s great if we have a system that does all that for us, but we don’t have to, if we just have templates that are reusable, that’s valuable on its own.

If we have a repeatable process that’s not a methodology, right? It’s not fixed, but it’s just a way of working that is valuable because it’s bringing that knowledge back. So I just wanna take you back to something that you said, So if I take this idea of term, in fact having massive value and that we get that with a subject matter expert, and by documenting it in that format.

That context is able to be seen and understood by many people other than us. You then said that it’s also a way of getting alignment. So if I get that term, in fact, if I get that fact-based model for inventory from three different domains,

How do you deal with the alignment problem?

Marco: I can illustrate it by an example. And let’s stay close to the examples that we already mentioned, but it’s more powerful, more generic and more diverse than that. But I think we would need a podcast of another two days that would explain all of the ins and outs, but, so really to just show you how that would work. And I have to for the listeners doing this in an audio only podcast, I’ll try to make it as visual as I can. So when I say Marco Ban lives in Urich, which is the city of, where I live, is that would be effect that you and I can agree on and, me and my wife, we definitely agree upon that.

So let’s consider that effect and the statement that is to hold some truth value there. But there’s something else going on because Marco Warban lives, INTA is a state statement that, my wife lives in nut, my kids live in, so there’s a bunch of statements.

They all express something that we can classify as the city of residence. So by stating multiple examples like that, we can type those kind of statements as city of residence as the fact type. Now within me saying Mark of wo lives inre, I actually embed knowledge in there, even though you and I can agree upon the actual fact. I’m also saying, wait, Marco Ban is the citizen, is the city. But it goes a little deeper because my citizen is not really a citizen. It is just how I identify a citizen. And in that identification I can see, wait a minute, there’s a first name and there’s a surname. Similar with the city of Urich. It’s not really a city, it’s we’re representing the city by storing the name of the city. So you can see that if you can visualize that there’s knowledge, almost like a graph in there where I started with the city of residence. I gave it the semantics lives in, but it also has structure. It has the citizen, it has the city, it has the first name, the surname, the city name, and all of that ties together into this single fact statement. Now I can populate that with different examples. I can give my wife a position in there and my kids. And so it is populated with all kinds of example data and then the subject matter experts is then post with a series of questions. Could it happen at the same time that Marco lives in re as ma Marco lives in New York?

And then he would probably say, no, there’s something wrong with that. By going through these interactive sessions, which is almost like a gamification of the interview if you will, is you discover the business constraints and then by discovering the business constraints, that will lead to a certain structure.

When it comes to data modeling. If I can live in only one city, then the city is probably an attribute in the citizen’s table. If I can have multiple cities where I can live because that’s allowed in our register, then I would probably need a linking table in the end in physical model. So these constraints steer how the data is structured. And this is the interesting byproduct and I’m not sure if I’m still on track of their question, is that. In the interviews with subject matter experts, we can find ourselves very easily in hours long sessions about, what is a citizen. But as soon as they cannot give me a proper example to illustrate what they’re talking about, I’m talking to the people that are working outside of their scope of expertise. So that helps steering that. So there’s an organizational alignment in my efforts to find the data, illustrating the information. Now, the alignment on the other hand is now I start identifying Marco at some Gmail address lives in. So now I’m identifying the same citizen, but I’m using an email address. Now, obviously, in, in official organizations and registers that would never do, but, let’s suppose we have a small tennis club and it’s fine, so what I find now is that I still speak of city of residence. I still speak of citizen and city name, but I don’t have first name and surname.

So suddenly that citizen, where it used to be first name and surname now is an email address, but it still identifies a citizen. So what happens in the information grammar, if you will, is that there is something introduced called a generalized object type. My citizen can either be identified by first name and surname or by email address. So in the modeling part, it’s very easy to find statements that either generalize, which means that it allows different ways of identification for it, or different ways to talk about it. I now, I am presented with a data challenge because which combination of first name and surname goes with which email address. So again, I need a different fact statement that now would introduce, Marco W has an email address called Marco such and such at Gmail, which links the two keys. So nothing in my communication has to be altered to support alignment of different ways of identifying it, doing data mapping, just as part of the verbalization. I have a department here that only works with names. I have a department there that only works with Gmail addresses. I can make them talk to each other ‘ cause that needs to happen sooner or later. And the way that they talk to each other is say yeah, you’re right. This market woman corresponds with that email address because I have proof of that.

So then suddenly you have a mechanism introduced in the communication on how to identify certain entities in your data administration in a unified way. So this is different examples on how these alignments work on both semantic level, on a data level, on an identification level. In short.

Shane: I was thinking about it slightly differently, but it’s exactly the same process, I think. So let me play it back to you where I think I got to. you are talking there about, okay, we have this term and the term has the same context definition but the facts that identify that term are slightly different, right?

And we can then do some alignment where we see these different identifiers.

Marco: Yep.

Shane: The one that I was thinking about is where a domain or a business unit has a completely different definition for that term. And another one does. And we identify that. So let me give you an example that’s real for me right at the moment around citizenship or residency.

Marco: Oh.

Shane: So I think I know what made me a resident in the uk. It’s when I got a certain kind of visa and I entered the country. And as soon as I did that, that’s the rule that tricked the tick in the box that I am a resident of the uk but when I deal with tax residency, it’s a different set of rules.

And so they’re slightly different, I have to live here, but then also I have to make sure that there’s certain things I don’t do anymore back in my original country of tax residency. And so they’re both residencies, but they’re slightly different. And then how would I articulate that using term and fact, How would I fact based modeling it. And the thing that you talked about is this idea of business constraints. If I can describe the business constraint of what our residency is versus the business constraint of a tax residency, again, now I’ve got two patterns and I can look at those two patterns, those two constraints and say they’re the same or similar or they’re very different.

And in this case I’d say they’re different, One is around how my financial transactions work and one is where my ass sits when I have breakfast for the majority of the year, ‘cause I can spend a certain amount of time outside the country and I am still a resident of this country.

And then I think the other thing that this Pattern gives us, which we know happens a lot because we see humans do it, is as soon as I give somebody those terms and facts. And a set of business constraint, a set of descriptions of how they behave. Humans love to point out exceptions, especially subject matter experts.

It’s yeah, you could be a tax resident in the UK if you do that, but actually if you do this one other thing that nobody ever tells you about, actually you are not That’s the exception. Oh. And by the way, system A knows about that, but System B doesn’t. And humans are really good at pulling out that.

I dunno, what would you call it? The knowledge that only they have. And like you said, when we used to work for organizations for 25 years, that knowledge state in the organization, now you’re lucky if it’s five. So that context, that knowledge of those exceptions disappears. I can see how this idea of defining or articulating business constraints, identifying exceptions, finding them to that term, in fact Pattern in an artifact that’s repeatable.

We can now shortcut, like you said, the need for a data expert and a subject matter expert to spend a week in a room going through this magical process that only two people can do. And make it a little bit more, not democratized, but a little bit more accessible and repeatable.

Marco: it’s an interesting example, but again, it’s, it touches the exceptions. Again, your example in itself is an exception. And it’s, it is too much to say about exceptions. But even talking about it as you just did from a tax context, Shane, the citizen dot. So even in our semantic and in our language use, oh, we already start distinguishing that. And then it comes back to do we identify the citizen in a text context the same as the citizen in a legal context. And to tie it back to my previous example, are those two the same citizen? And all three of them are different domains. There is the text domain, there’s the legal domain, and there is the domain where we might want to match if this is the same person, for whatever anti-terrorist rule organization or whatever. So there’s different domains and every domain has different rule set. So blankly calling them all citizen because in mentally we can say, yeah, it’s the same person, it’s the same citizen. But data administration wise, the data administration of identifiers for a citizen are not the same as the data administration for identifiers for a citizen in a different context. And I think again, that’s the big separator between and it causes a lot of confusion in interviews and workshops, is that. We humans unify that because we see that the reality, it is about one person. But what distinguishes that is that we need to talk about how we talk about the data. And that is not the same thing as the reality. And by separating those out, it makes it, in a way, it makes it easier to say, okay, but are we talking about the same data administration?

No. Then we’re separating those out and if we are talking about three different domains that need to come together in one data administration, then we need more semantics. Distinguishing the three.

Shane: a couple of things I want to loop around there. So again if we go back to the term actually, there is a citizen and a , physical residency and a tax residency because I’m actually a citizen of New Zealand still, but I’m resident physically in the UK and my tax residencies coming with me. But again, it’s not until we, we start using term and facts together that I can articulate that those are three different things, and it’s the business constraints and the exceptions that tell me there are different things. one of the things that I find interesting is this idea of focusing on the complexity and modeling that, is the area that’s gonna cause you a problem.

So if you ever do data bulk training with Hans and WinCo Brockman, they’ll, and I dunno if they do it anymore, but they used to talk about Peter the fly. And so the example would be if I am sitting in this ice cream store and I see Bob come in and order that ice cream and there’s an order id, So I can say when I put term, in fact, there’s a an ID in there of 1, 2, 3, 4, which is the order number. And if I want to know whether they actually got the ice cream. Is a separate part of that process. And on Peter the fly, I can see the ice cream being handed to Bob. So I know it happens if I’m in the room, but if I’m looking purely at the data, at the facts, I see nothing because there is no handover,

there’s no delivery ID that they got the ice cream. So I’m gonna have to infer that if there was an order and no refund turned up, that I’m inferring that happened, but it’s not a fact. And so I think, again, those terms and facts tell our stories and then as data modelers we can look at the exceptions that we know we need to worry about.

But I wanna go back to this idea of domain because it’s one that I struggled with a lot and I still do is a domain boundary can be anything. It can be a business unit, it can be a series of core business events. It can be a process, it can be a use case, it can be a team topology it, a domain is just a boundary where you say it’s in that boundary or it’s not right.

It’s in this domain. It’s in that domain. And I hadn’t thought about using the term fact and business constraints as a way of defining boundaries. For domains. So if I see, a term, in fact that’s all around my citizenship and I see another term in series of facts and business constraints around my residency and I see another one around tax residency and they are different, then I can use those as domain boundaries.

They might be too granular for the intent that I want to use it for. But what we’re saying is they are different. You write them down as words and numbers you can tell they’re different. So that gives us a form of boundary. And so that’s really interesting because it gives us a Pattern,

it gives us a formula of how we can say that this sits in boundary A domain A, and this sits in domain B because of these rules. And I find that really intriguing and valuable ‘cause it’s solving a problem that I’ve been trying to solve for many years. ‘cause it’s annoying me.

Marco: Yeah. It’s, it is. So there’s two you’re right there’s two big areas where you can see there’s a separation of domain. And so rules is one of them. It’s in a hospital systems for example, you might wanna need somebody’s birthday to be able to put it into the computer.

As we had this kind of operations, these treatments, it needs to go this to his insurance company and all of that. But if you’re brought into the emergency room unconscious, you have no idea on you. You’re still being registered as a patient. So the rule is entirely different, but yet we have a patient number somehow. And the definition of the patient is clear across the whole hospital. So rules determine some sort of context. Or, if you come in with an appointment, they probably know your birthdate. If you wanna send it to the insurance company, they have to have your birthdate. The emergency room doesn’t really care. So how do you align all of that? So then you see, again it’s we’re unified in the language, we’re differentiating on the rules, and somehow we have to integrate systems. The most important part is that independent of which system is being built, we need to figure out how we communicate first.

So that language always goes number one. And that’s basically the what fact-based modeling does. It allows people to talk about it from their context, and then given that specific context, you add specific rules for that context. The example where can I live in multiple cities, municipality wise, no, you cannot. You have to be registered in one municipality. Now, in a more generic way, you can have people registered to different places. Sure. I have an office here, I live there, I have a vacation home there. And it’s yeah, different places. But on a municipality level where it becomes more context specific, there is a rule that says you can only register in one municipality. So there’s that too. There’s, there is a way to generalize in a more abstract way. If Ft has been doing that for years, where they introduced the party model, is it a person, is it an organization? Is it, we don’t know, is let’s call it party. We’ll give it an artificial key and we’re good. That’s just the way to keep the IT system running. It has nothing to do with semantic or integration or alignment or whatsoever. It’s just a technical solution because we didn’t get the business meaning in the first place, or we are not specific enough to a specific context. So these problems will always occur. And I think that separates the data modeling from information modeling is where the data modeling is. Do we find alignment in how we need to build the system? Whereas information modeling is, do we find alignment on how we communicate about the data?

Shane: so again, you are making a context differentiation

between the audience. That’s the consumer of what we are creating. And you are saying if it’s stakeholders who aren’t data experts or IT experts, then we’re information modeling. If it’s data people or IT people then we are data modeling,

And the ability to have both languages, but then a mapping and sharing across those languages of where the real value is. And so like you, I’m not a fan of thing as a thing. I don’t agree we should ever use that term in our information models. We should never use party entity thing as a thing.

A thing is associated with a thing as a generic way of describing context to a stakeholder. I also don’t think we should put that in our technical systems. Years ago when we had mainframes and we had no memory and we had no disc and the infrastructure was expensive yes, it had value to us. Right now, the most expensive part of our systems is the humans and understand that context.

And as soon as you design a system with thing, as a thing, and that context lives nowhere else, I now have to spend a massive amount of expensive time trying to understand what the hell, how many things you have, how many things they are related to, and how many things those relationships are.

And that is an expensive piece of work. And I just can’t justify doing that anymore. But as you can tell, I’m slightly opinionated on that one. And it’s also, if I come back to the way we do that information modeling the grain of it, The detail we go to is interesting

because if I do it just based on terms customer orders product, it’s very different doing it based on terms and facts customer bob orders ice cream

Marco: Yes.

Shane: And so what you are saying is actually you are bringing more detail, a higher level of grain into that information modeling process earlier because it has value, so you’re doing more work upfront because you’ve found ways of taking that work that’s done early and automating some of the downstream work in terms of the technical implementations.

And so bringing, from an agile point of view, you are doing work upfront work in advance, which could be waste, but you’re found a way of taking that work and reducing the waste further down the value stream.

Marco: Yeah. Correct. It’s really that, and for those who are interested in this a lot of the information can be found on the website called casetalk.com. What it shows, and this was developed in in, like I said in the seventies, all the way up to 2000 is it’s not just, oh, how can we capture the language?

But it was really, how do we talk to the domain expert to come up with the appropriate IT system? And I think what happened really is that it is such a rich and detailed environment where people modeling traditionally with business knowledge in their heads doing the IT itself, which was very close bound to, organization. When the first computers came in, it’s like it was usually the domain expert that got an IT training. They knew the context, but nowadays it scales up so much is that you are an IT professional. You have no idea about any business. You just, your business is it. So getting back on that and trying to find that alignment with business is, it is of increasing interest, but it’s not the majority.

A lot of new young professionals base their efforts on the tools and the ability of tools and not as much as are we doing the right thing for the business because they don’t really care. They were not educated as such. There’s a massive gap there that where business looks at it is like you’re, you are the expert, so you tell me and then there’s this rift and. You mentioned data Vault a couple of times where, traditionally the hub is the natural business key, right? It’s not a technical key in the source system. So what is the business key? Then you have to talk to the business. And the rich information modeling does with all the fact base is that already mentioned Marco Ledge and Nutra.

So I already have the natural business keys right there. And with a push of a button, it can then be generated into a citizen table and a city table and even have artificial keys with minor annotations like city of residence. We might want to keep a log in time, we might wanna have history in there, but also when is he planning to move to the next city so it becomes bitemporal. And these are very simple flags in the information model that can be generated to a data model that says, did you want a data volt model or a normalized model, or did you want a adjacent schema? So the physical parts become automatable. The data model becomes automatable and having all the semantics and verbiage and examples, it makes it verifiable and readable by the business. And so that really what it ties in and some experiments show that precisely that combination is the real power to keep LLMs grounded as well.

Shane: I definitely agree on the LM front. We know that if we pass at the terms definitions of the terms, the facts, so data examples around those terms and their relationships and natural language business constraints into those lms, we get a much better response when we want to do a task.

Marco: Yep.

Shane: So that context is really important.

And that’s why, it’s interesting watching all the, bi semantic layer vendors try to say they’re context engines and you’re sitting there going, but you’re just at the end of the chain, you’ve just got metrics and maybe some definitions, but the richness is all sitting on the left of our value stream.

It’s all around problem ideation, discovery design. It’s not physical implementation of our consume layer for your cube. Yes, it’s got some value And so I’m in really interested to watch the reinvention of the market yet again. ‘cause as you said technology is often what people get taught.

A number of times I’ll talk to a data science student who’s been taught Python

And you go back and you go, but. How do you understand the business problem? How do you understand the value you’re gonna deliver if you build that ML model? And we’ve seen, as you said, we’ve seen over time data teams that don’t add value don’t survive.

Marco: True. And I remember an interview that was told that we’re, and not to talk them down, but it really points at the lack of education as well, or, the business debt and the technical debt. It’s just people are being trained in tools and in technical approaches where some of the analysts really said, what is your highlight of the day?

Is that when they discover insight, it’s like insight. Should it not have started with the insight as documentation, or what are we really doing instead of let’s discover it. That is, like you said it’s the end of the chain while everybody shouts. Shift left shift left. It’s yeah, why?

Because that’s where it started and that’s what we lost. From my perspective, it just starts with can we talk to each other and are we writing that down? How we do that? Because that’s what we need to do in the end. And whatever it system we built, whatever dashboard is being built, it actually serves to better communicate about what we are really doing. So it all ties back to that. And yeah, there’s a never ending story because the LLM is the next silver bullet. It’s gonna solve all our problems. And it’s not, it’s helpful, but it’s not the silver bullet. ‘cause we still need to get the authentic story, not the fabricated story.

Shane: Yeah it’ll help us understand where the context differs but it won’t help us actually define what the context is.

Marco: Yep.

Shane: At the moment. from the stuff I’ve done with it. Oh maybe the, the next generation a GI version will, or, maybe we all end up with standardized context that every business follows.

But we know that’s not true either, right? We saw that with tools like SAP, where it’s implemented vanilla and then $50 million and five years later there’s a bastardized customized version because that organization is different with air quotes.

Marco: and I can illustrate that by fairly simple examples is that, I mentioned that somewhere else. It’s like there’s not a bank in the world that I didn’t purchase the IBM banking model at the same time I dare any bank in the world to actually have implemented it. and that points to a massive gap is that, to be able to implement it, you first have to know what you already do. Which is a massive dilemma ‘cause nobody has the information models and then you are presented with a technical model, like the banking model that says, everything will fit in here.

It’s okay, but what do we have that actually fits? So there’s a massive dilemma there. And then in the end every bank will try to do it a little bit different. So they have an advantage over the competition. So they don’t really want to confirm to one standard, which points back at. There is no real universal Pattern because everybody tries to give it their own little edge, which means you have to capture that edge, not just build something that you think will fit.

You have to be very specific and in that I’ve seen systems database was designed with rigor and the software was developed three times over, but the database didn’t change. What happened is. A new wave of tech came, it used to be mainframe, then it became Windows, then it became internet, then it became mobile Data did not change the way the technology work, changed the organization, changed the business processes because, we’re not having a physical storefront for the bank, but we now we have a mobile app. So the process of working with the data changed, but the data itself didn’t change. So there’s a lot of dynamics going on and it really shows the importance of getting the data right and don’t throw away the story that came with it so that you can actually reinvent all the processes and all the software on top of it without losing meaning. But it also points at the fast changing world where we perceive everything changes all the time. So we cannot sit down to do a proper information model and have a data model set up, et cetera, et cetera, because we’re in a hurry. We need to deliver what? Nobody realizes that if you sit down long enough to have that information correct, you have the data model correct.

And don’t throw away the story that it will definitely give you a return of investment.

Shane: I’ve gotta say that the IBM data model was a masterclass in sales, The fact that you could sell a diagram, a picture for millions of dollars that nobody ever used, apart from putting it on their wall. That is a masterclass. But I go back just to close it out, I go back to that idea of terms and facts.

So if I have a retail bank, had a store. The terms and facts might have been customer Shane has an account. 1, 2, 3.

If I became a mobile only customer when we changed technology, I might see the term in fact change slightly, where it’s customer oh seven five, yada y has an account 1, 2, 3.

Now I can look at those two lines and I can see something’s changed.

The fact that relates to that term has changed and now I can have a conversation about is that just what you are showing me? And in the background it still says Shane, or did it never say Shane in the real data? It was always customer id. 1, 2, 3, 9, 2, 4. There’s a whole lot of conversations I have, but I know that something’s different and now I know what to have a conversation about with that subject matter expert.

As you said in the past, the subject matter expert, the data person and the IT person was the same person.

Then it became the same team. Then we became a business and IT team, and now we are a business subject matter expert team, a data team and an IT team. We are, we’ve team topologies have got more matrix E, more bigger, and that separation causes some problems.

So by using patents and patent templates and artifacts and shared language, we can close that gap again. And for me, this idea of fact-based modeling, this idea of binding terms and facts with a set of rules, with a set of exceptions as context is really valuable. We can use it in so many ways.

So just to close it out, if people wanted to hear more about this, read more about this, find out more around fact-based modeling, where do they go?

Marco: I think the quickest way into it is to just go to I personally wrote a little book which is published by techniques publications called Just the Facts. It tells the story and names a few examples that I mentioned in this podcast too. It gives you an overview from management to architecture, modelers and developers, and how communication and effects weave through all the disciplines. Obviously CaseTalk is the software tool to support all of that. But you will find links for actual books if you happen to have a copy of the DMBOK by DAMA . The older edition has a crippled article about it. The version two latest edition has a slightly improved article about it. It’s on Wikipedia sources enough, but the good starting point would be casetalk.com.

Shane: Excellent. Alright, thank you for that. I’ve got a new set of patterns and templates I need to go and read a lot more about. It’s gonna be me over the next few months again. But thank you for that

Marco: good. Thanks for having me and talk to you soon.

Shane: I hope everybody has a simply magical day.

«oo»

Stakeholder - “Thats not what I wanted!”

Data Team - “But thats what you asked for!”

Struggling to gather data requirements and constantly hearing the conversation above?

Want to learn how to capture data and information requirements in a repeatable way so stakeholders love them and data teams can build from them, by using the Information Product Canvas.

Have I got the book for you!

Start your journey to a new Agile Data Way of Working.